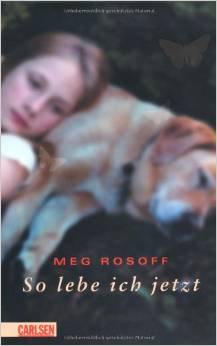

Meg needs no introduction from me, that’s for sure. But in case you wanted a reminder, she wrote that book they made into a massive movie, you know, THAT book: ‘How I Live Now’…BUT she has written many other books too and is the winner of a shed-load of prestigious awards: Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize, Carnegie Medal, Branford Boase Award etc etc and a nominee of a bunch of others.

My personal favourite book of Meg’s happens to be my daughter Poppy’s favourite, which we’ve been reading since Pop was a toddler and that is the deliciously yukky: ‘Meet Wild Boars’:

My other favourite book of Meg’s – and one that doesn’t include boar poo, as far as I can remember – is ‘What I Was’, a lovely, evocative story set on the mysterious eastern coast of England. I read this the year Poppy was born and it still lives in my memory now as a haunting tale.

For more background on Meg, read her CV here, if you want a good laugh, especially the bit about how many times she’s been fired:

http://www.megrosoff.co.uk/about/cv/

‘Picture Me Gone’ is Meg’s latest novel and is the story of Mila, a girl with exceptional powers of observation and empathy, who goes on a road trip with her dad to search for his missing friend. I read it and loved it, so I asked her a few questions about it and she very kindly answered them:

‘The past is foreign country: they do things differently there.’ This opening line from ‘The Go-Between’ reminds me that some people may feel their childhood is a bit of a mystery to them. Adults often forget how it was to be a child. How do you manage to keep in touch with the child or young person you were, in order to create your central characters?

I’m still the person I’ve always been and adolescence was a particularly vivid time in my life, so I don’t have to remember — it’s still with me.

In ‘Picture Me Gone’ one of your characters is described as ‘gazing at something inside his head’ – how do you reach that quiet space in your head to write? Can you write anywhere, any time?

I don’t need a particular place or time to write, but sometimes I go a year or more without writing much of anything. I have to wait for the book to come to me.

At one point in the book, Mila talks about the curiosities involved in the art of translation between languages. I’m very interested in your thoughts here on translation. Is some of this influenced by your experiences of having your own work translated?

I’ve become close to both my German and Dutch translators over the years — my Dutch translator told me that she translated all of How I Live Now and then threw it away and started again because she didn’t get the voice right. It’s a weird job translating someone else’s voice, and translators rarely get much credit or payment.

There is talk in this novel of disturbing images in one’s mind. Do you feel the same as Mila on this one? Can a person have too many disturbing images in their head? If so, how does that affect the way you write and your subject matter, and also perhaps your reading/viewing habits?

My head is full of dark stuff, it’s just the way I am. And of course that affects everything I think and write. I’m a cheerful depressive.

Mila notices everything. Were you a bit like Mila when you were a kid? Is that how you see a writer’s mind, perhaps?

No, I’m not at all like Mila. But my daughter is — she’s incredibly observant. She notices and files away everything.

Meg and her daughter Gloria.

Later in the story, Mila tries to imagine herself grown up and fails – I remember trying to do this myself as a child and equally failing! The title of the novel – ‘Picture Me Gone’ – is this a suggestion of this theme within the story, this idea of loss, of something lost when the child becomes an adult? If so, do you feel this always has to be the case? Or are there ways in which we can lessen or ameliorate it somehow, or try to regain it in later life?

I’m very interested in the idea that at whatever stage of life you’re in, you find it nearly impossible to imagine the next stage. No one imagines that they’ll be old and senile, much less dead, and kids have an even harder time drawing a line of continuity between being young and being old. When in fact most of us feel more or less the same inside at every age. I don’t believe anyone ever “becomes an adult.” It’s an illusion that has more to do with having a mortgage and paying bills than being a different person.

Thanks very much to Meg Rosoff for her illuminating answers. As ever with books, the work of many authors gets put on a particular shelf and labelled as this or that genre, or for this or that audience, yet we all know deep down that there are some special books that don’t fit in a pigeon hole and insist on busting out and just being themselves. So, if you thought Meg Rosoff novels were about Young Adults and for Young Adults and those alone, think again, pick up one of them and read it. Whatever age you are and whatever genres you like, it’s damn fine writing and I reckon you won’t be disappointed.