I’m delighted to welcome Sarah Sykes to my blog this morning in a fascinating interview about her brand new debut novel, Plague Land. I enjoyed reading this hugely – a compelling murder mystery with a stark yet poetic style, a vivid sense of place and a period of history with which I wasn’t very familiar, and I’m now hooked on it!

[1] Your research into the period seems impeccable. I was most interested in the details about such things as food and medical matters. What kind of sources did you use to find out about these aspects of daily life?

There are very few handwritten cookbooks that survive from this pre-print period, so I mainly used secondary sources to research diet – books and websites that describe medieval food, menus for banquets, table etiquette etc. I also studied images in the margins of medieval manuscripts, as kitchens were a favourite subject for illustration. Boar, venison, rabbit and fish are often seen roasting on spits, being turned by a bored-looking scullion, (though it’s important not to put too much store by these images, as meat formed a very small part of the average person’s diet.) Chaucer talks regularly of bread, ale and wine – which is a much more accurate description of what people ate – the poorer ones anyway – with ale supplying a substantial percentage of the calories a person needed to survive. And then, of course, there was pottage – a type of vegetable and meat soup that was an absolutely staple part of the diet for rich and poor alike. Pick up any medieval novel and people will be eating pottage!

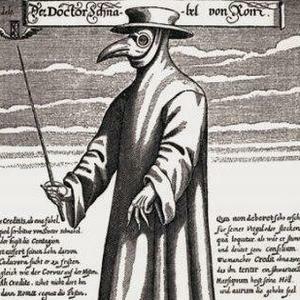

Medicine in 1350 centred very much around the teachings of Galen – the theory that the body is ruled by four ‘humours’ that need to be kept in balance. There is much written on this subject, so it was easy to research via books and the internet. Once again I drew on the graphic and sometimes macabre imagery in manuscripts for inspiration. Depictions of bloodletting; the repair of anal fissures; even caesarean births. Through my research I discovered that pretty much anything went in the world of medieval medicine. There were all sorts of weird and wonderful cures for the Bubonic Plague for example – including smearing the lanced buboes in dried excrement and drinking your own urine!

In the unlikely event that the physician cured you, then it was a miracle. If you died, then it was God’s will. The physician was rarely blamed for poor care, or even the death of his patient. For my own part I would rather have visited a monastery if I’d been ill, where the monks had a good knowledge of herbalism – often based on their translations of ancient Arabic and Roman texts. If the use of herbs did not relieve the symptoms, at least the treatment was less likely to kill you.

(An interesting aside here, that in my next novel Song of the Sea Maid set in the C18th, the idea of the 4 humours still dominated medical thought 400 years later and was used – completely erroneously – to explain the causes of scurvy, with disastrous results, of course.)

[2] Your writing delivers a very visual sense of place – did you find yourself living in the period in your mind, while writing? Did you use a picture wall or something similar?

I’m very lucky to live in the setting for Plague Land – a part of Kent which is remarkably untouched by modern life. A surprisingly large amount of medieval timber-framed homes, barns and fortified manor houses have survived in the high weald, and, wherever possible, I’ve tried to get inside these buildings and just sit – to imagine the light, the smells, the sounds. Of course, conjecture plays an enormous part in this process, as most buildings have been renovated or modernised in some way or other – but I was able to visit the wonderful Weald and Downland Open Air museum near Chichester, where many medieval buildings have been saved in their original form. This was a joy!

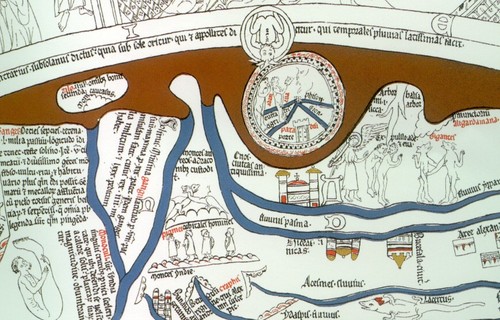

I didn’t use a picture wall as such – but there is an image to which I often return. It’s a touchstone for me – the drawing of two dog-headed men on the mappa mundi in Hereford Cathedral. (Look to the middle, right hand side of the map.) This small image, more than any other, conjures up the medieval mind for me – a place of enchantment and wonder, but also superstition and fear. These two strange-looking creatures were the original inspiration for Plague Land.

[3] What choices did you make when it came to rendering the speech of your C14th characters? Did you update/modify how dialogue would have truly been back then, and what aspects remained faithful to the period?

This was very tricky, and thank you for raising it. I read (rather I tried to read) Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the original Middle English, because Chaucer was writing about 30 years after Plague Land is set. However – Middle English is incomprehensible, unless spoken aloud, so that was a non-starter. I chose, in the end, to give a flavour of archaic speech – and hope that this didn’t sound strained, cod-medieval or comedic in an Edmund Blackadder kind of way. This meant a careful choice of vocabulary in places – and the constant looking up of the etymology of words, to ensure that their origin was not much later than the 1350s. One example of this would be the word ‘side-tracked.’ I had used it in an early draft, before realising that the term derives its meaning from the railway industry.

[4] As well as being historical fiction, this is of course a detective/crime story. What methods did you use in your planning to work out the mystery plot?

There is a craft to writing a crime novel – certain conventions that the reader expects – such as a murder early on, a range of suspects, the inclusion of red herrings, suspense, and a plot that moves with momentum towards a surprising, but inevitable conclusion. I’ve read many crime novels and wanted to make sure that I hit as many of these important markers as possible – so there was a lot of plotting and planning (some of it with different coloured highlighter pens and long pieces of paper.) I’ve heard some crime writers don’t know the identity of the culprit before they set out on their novel – but I would find this impossible! I even wrote my big ‘reveal’ scene before writing most of the novel – to make sure that everything led up to that one climactic moment.

[5] The plague itself names the book and is of course a running metaphor throughout. Could you explain what you feel the plague metaphor stands for in terms of the characters and the period? (if you can do that without spoilers?!)

The word Plague is so emotive – conjuring up death, panic, desperation and desolation – all of which topics exist in the novel. Initially, however, I felt the word was too obvious to use. Plague Land was just my working title – and I hoped to come up with something much more literary and clever sounding! But, as the novel progressed – the title just seemed to suit the novel more and more. And not just because of the literal meaning of the word ‘plague’ and its obvious relevance to the Black Death, but also because of the way Oswald is plagued… with self-doubt; with responsibility he doesn’t feel ready for; by a hell-fire priest who’s trying to crush him.. and by the women in his life – a nagging mother who is always on his case and a sister who resents his power and position. I stuck with the title – because it does encapsulate what the book is about.

[6] I’ve just finished writing a novel set in the C18th. There were certain aspects of the period that really appealed to me – such as the quaint language – yet others that made me very grateful I live now! What are your feelings about the C14th? What do you feel we’ve lost and gained since those faraway times?

In all honesty, I’d love to travel back in time to 1350 – but then I’d want to return pretty quickly. It’s often said that life was nasty, brutish and short in those times – and in many ways it was. We’ve gained sanitation, medicine, literacy (most people in 1350 could not read.) We’ve eschewed ignorance and superstition; the dogged, dictatorial supremacy of the church; unquestioning deference and obedience to the ruling classes. We have democracy, equal rights… I could go on and on!

So, what have we lost? The simple life, I suppose. Living with the seasons and nature. Even something as basic as just being outside. In those days, people spent a lot of their time in the open air of the fields, the streets or their gardens. Their cottages were small and cramped, so they only went inside when it was cold or they wanted to eat or sleep. They had extended families and very close communities that gave companionship and security. They were fully occupied with their work; they had the satisfaction of growing their own food and creating their own homes, clothes, tools etc and they used their imaginations and memory in a way that we no longer do. As long as they were healthy and reasonably fed, I have a suspicion that people were happier.

Thanks very much to Sarah for her brilliant answers and I hope it helps spread the word about her super novel. If you enjoy Plague Land, look out for The Butcher Bird (great title!), her follow-up novel starring her detective Oswald, due out October 2015.

Keep up to date with Sarah at her website (very attractively designed!) here:

and see another interview with her by fellow historical novelist Antonia Hodgson on the excellent historylivesathodder here:

http://historylivesathodder.tumblr.com/post/98378343274/antonia-hodgson-interviews-s-d-sykes