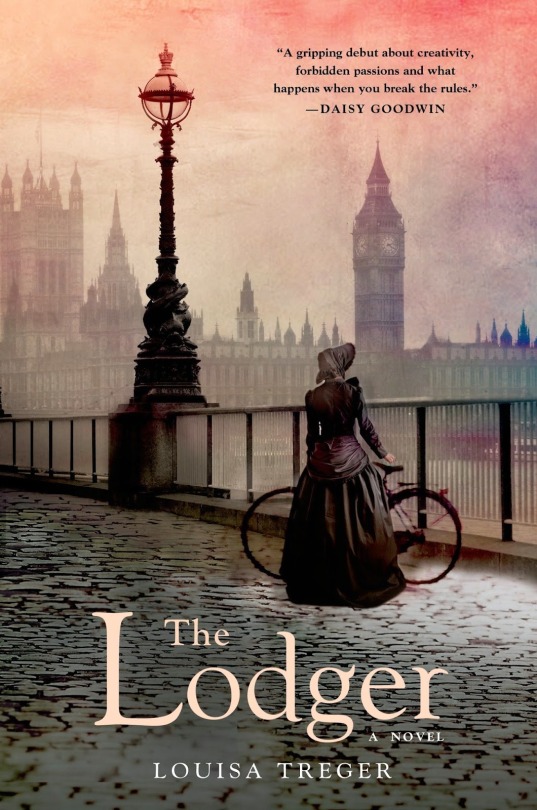

I’m so very, very happy to welcome to the blog wonderful novelist, dear friend and fellow Prime Writer & Historical Writers’ Association member Louisa Treger. Louisa’s first novel, The Lodger, came out last year and what a beautiful novel it is. Firstly, here’s the blurb:

Dorothy Richardson is existing just above the poverty line, doing secretarial work at a dentist’s office and living in a seedy boarding house in Bloomsbury, when she is invited to spend the weekend with a childhood friend. Jane has recently married a writer who is hovering on the brink of fame. His name is H.G. Wells, or Bertie, as they call him. Bertie appears unremarkable at first. But then Dorothy notices his grey-blue eyes taking her in, openly signalling approval. He tells her he and Jane have an agreement which allows them the freedom to take lovers, although Dorothy can tell her friend would not be happy with that arrangement. Not wanting to betray Jane, yet unable to draw back Dorothy free-falls into an affair with Bertie. Then a new boarder arrives at the house- beautiful Veronica Leslie-Jones- and Dorothy finds herself caught between Veronica and Bertie. Amidst the personal dramas and wreckage of a militant suffragette march, Dorothy finds her voice as a writer.

I absolutely loved this book. I’m a huge fan of the Edwardian period and I’d just finished writing my Book 3, which is set in the same period, so I was certainly in the right frame of mind to read it. For example,

I was excited to see H.G. Wells’s novel Ann Veronica referenced in the book. I read it as Edwardian research for my own book and really enjoyed it. But my admiration for Louisa’s book was so much more than just the setting. Louisa has such a beautiful style, observant, pensive, with a kind of luminosity. Just lovely.

It’s got such acute psychological insight & it’s very brave, the way it talks about sex, for example. It’s like an anatomy of a relationship. I think Louisa’s prose is stunning. Very sensuous & beautiful descriptions of weather & how moods change. It’s very insightful on the price of personal and artistic freedom. Bravo all round! For me, I think Louisa Treger the novelist is a class act & I can’t wait to see what she comes up with next.

I think she is a very fine writer indeed.

[1] Please tell us about the moment you first encountered DorothyRichardson and her writing. What appealed to you and drew you in?

I stumbled on Dorothy Richardson by accident, while researching Virginia

Woolf on a hot dusty day in the University of London Library. Opening a book at

random, I found a review by Virginia about a writer whose name I didn’t

recognise. This is what it said:

Miss

Dorothy Richardson has invented … a sentence which we might call the

psychological sentence of the feminine gender. It is of a more elastic fibre

than the old, capable of stretching to the extreme, of suspending the frailest

particles, of enveloping the vaguest shapes…

I was riveted. Who was Dorothy Richardson? How had she come to reinvent

the English language to record the experience of being a woman? Further

investigation led me to her life work: a twelve-volume autobiographical

novel-sequence called Pilgrimage.

It was the originality and courage of

her writing that struck me the most. Her

aim, in her words, was to “produce a feminine equivalent of the current

masculine realism”. She was fearless about smashing narrative conventions like

plot, structure and narrator – and she did this before anyone else writing in

English, before Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. She created a new, fluid way of

writing that rendered the texture of a woman’s consciousness as it records

life’s impressions. The novelist May Sinclair coined the phrase “stream of

consciousness” to describe Dorothy’s work.

Dorothy was just as fearless and unconventional in the way she lived as

she was in her writing. She couldn’t settle down and conform to any of the

limited roles available to women, but smashed almost every boundary and taboo

going – social, sexual and literary. The more I found out about her, the more I

felt that she was an extraordinary woman who had somehow been forgotten by

history, and her story needed to be told.

Dorothy Richardson

[2] I want to find out about how you chose the events of thenovel. How did you decide where in Dorothy’s life to begin and end in your

narrative and why that particular focus?

Perhaps,

before I answer the question, I should explain which events The Lodger covers! I

chose to write about a brief, dramatic period in Dorothy’s life, during which

she falls in love with H.G. Wells, the husband of her oldest friend, and has a

passionate affair with him. She explores her sexuality and independence, rejects

the conventions and restrictions of the age, and finds her voice as a writer.

The

early drafts of The Lodger were completely different to this final form. I

started in the same place: with Dorothy meeting H.G. Wells, but the first draft

had a longer time span; it covered her marriage to an artist called Alan Odle

as well. Also, there was a secondary narrative set in the present, a PhD

student who somewhat resembled me, researching Dorothy Richardson and

discovering a letter which changed the course of literary history. In fact, it

had clear echoes of AS Byatt’s Possession! But one of the problems I

encountered was that once Dorothy got married, her life settled into a

predictable routine, and it’s much harder to write interestingly about an

established married couple than about the intensely dramatic period of the

affair with H.G. Wells. In the end, my agent said: “This is the most

interesting part of the novel; I think you should make it the whole novel.” And

so I did, and everything fell into place from there.

H.G. Wells. Louisa describes those hypnotic eyes very well!

[3] Writing fiction about factual events and real people is a veryspecific challenge. How did you use research to investigate the personalities

and habits of the real characters, in particular, Dorothy and H. G. Wells? And

how did it feel when you decided to take artistic licence, if you did?

Before

I started writing, I read Dorothy and H.G. Wells widely. I read their novels,

letters and Wells’ autobiography. Unfortunately, none of the letters they wrote

to each other survived, but their letters to other people gave me a good idea

of what their voices sounded like. In this way, they took root in my

imagination and began to live and grow.

The framework of my plot was already there in

the biographical facts. Where it suited my purposes, I did take artistic

licence, and I have detailed these instances in my Afterword. Initially, it

felt like taking an awful liberty, and it made me question my responsibility,

as a biographical novelist, to the truth. I concluded that my most important aim

was to get inside the heads of my characters, to see the world as they saw it. Biographical

fiction gave me licence to achieve this. I invented conversations and details,

and occasionally bent facts, in order to animate

my characters’ conflicts, while staying as true to their personalities as I

could.

Wells and his wife Jane.

[4] I loved your use of language, particularly in description.“Words seemed to stream off the ends of his moustache and tumble down his

waistcoat”; “The dark figures and spectral faces of fellow passengers

loomed out at her as they approached, then vanished again, as though gulped

down by the besieging shadows”; “the white [roses] resembled pale

faces in the dimness, watching her”. So beautifully wrought! How do you

work on this kind of poetry? Whilst drafting or afterwards, in edits?

Thank you for the lovely compliment! My early drafts tend to come

out in great untidy clumps of words, not worrying about any of the fine

details, just getting the story out. I then go back and shape and polish, as

though the manuscript is a sculpture! So the answer to your question is: I work

on the language afterwards.

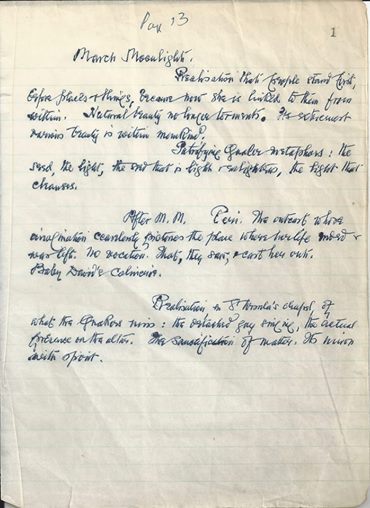

This is a real piece of Richardson’s writing that Louisa discovered by luck in a book. What a find!

[5] When Dorothy is struggling to find a new language in which toexpress herself in writing, it occurred to me that you were doing the same

thing with your style! How much was that a conscious thing, of echoing

Dorothy’s style in the narrative voice you chose for this novel?

You are absolutely right! One of the themes of The Lodger is how Dorothy

finds her voice as a writer, and I discovered my own writerly voice while working

on the novel. Having said that, I did absorb some of Dorothy’s style. It wasn’t

really conscious; it was part of wanting to remain true to her character.

the idea of becoming. Dorothy flowers as a person and more specifically as a

woman throughout the narrative, yet one senses this also has its costs and

losses. How did you feel about her passage to self-hood? Were the costs worth

it?

I felt that Dorothy didn’t have a

choice – or perhaps, a better way of putting it would be that her unconscious chose

her passage to selfhood. Throughout the novel, she is conflicted: torn between

being bohemian and being respectable, exulting in her independence yet

frightened by it, attracted to men and women, wanting close relationships yet

repudiating them. When an eligible doctor comes along,

offering security and respectability, she is initially drawn to him, but ends

up pushing him away despite herself. This

pattern is repeated in various forms throughout. The novel ends with Dorothy

achieving the hard-won freedom to be a writer. The costs were high, but it was

the only route she could have taken – the alternatives would have been a kind

of living death.

Children of the Kindertransport – Louisa’s next topic.

[7] Can you share with us anything about what you’re working onnext?

I am writing my second novel.

It’s about a girl who was part of the Kinderstransport – the rescue mission that

brought thousands of refugee Jewish children from Nazi occupied Europe to

safety in England. They left their families to go to the care of strangers, in

a foreign country whose language they only had the barest grasp of. They didn’t

know what would happen to them, or if they would see their parents again. The

novel describes how the girl and her descendants adjust to English life, and

how the trauma of the Holocaust doesn’t stop with the people directly affected

by it, but spreads down through successive generations.

Another haunting Kindertransport image. I can’t wait to see what Treger makes of this fascinating subject.

Thanks very much to dear Louisa for such excellent answers that give us a window into her writing process and the life of a little-known writer who deserves to be as famous as Virginia Woolf and the other modernists. That idea, of revealing hidden histories, is very close to my heart and certainly something I try to do in my own books. So, I’m very glad Louisa has revealed Dorothy Richardson to us and brought her to a new, wider audience. I wish this book wings, so that many people get to enjoy its beauty and insights as I have. 🙂

You can find out more about Louisa online here:

https://twitter.com/louisatreger

https://www.facebook.com/louisatregerwriter/?fref=ts

and you can buy her book right here – so what are you waiting for? Get clicking!