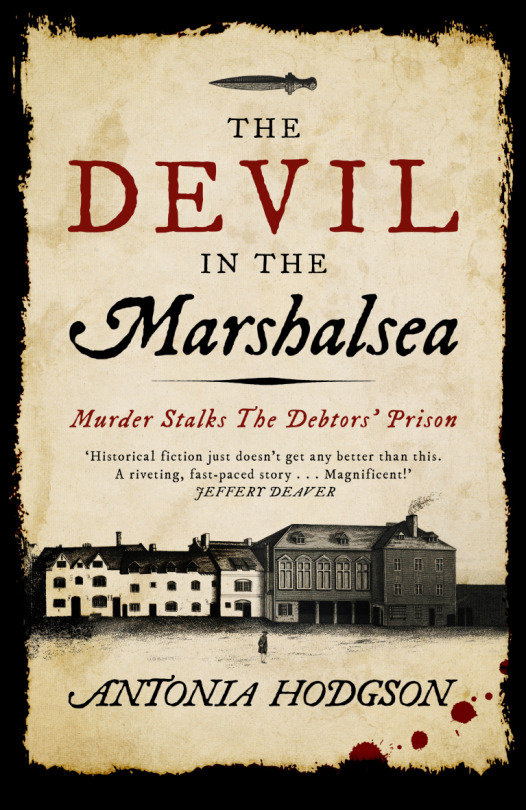

I’m delighted to welcome excellent historical novelist Antonia Hodgson to the blog today to talk about her two novels published recently to great acclaim: The Devil in the Marshalsea & The Last Confession of Thomas Hawkins. These two books follow the fascinating character of Thomas Hawkins through the mean streets of C18th London. This is the C18th that we often don’t see, with all the nasty bits. Great stuff!

Her first novel is out now in all formats, whilst her second is out in hardback and e-book and the paperback will be out this July.

Here’s the blurb for each:

London, 1727 – and Tom Hawkins is about to fall from his heaven of card games, brothels and coffee-houses into the hell of a debtors’ prison.

The Marshalsea is a savage world of its own, with simple rules: those with family or friends who can lend them a little money may survive in relative comfort. Those with none will starve in squalor and disease. And those who try to escape will suffer a gruesome fate at the hands of the gaol’s rutheless governor and his cronies.

The trouble is, Tom Hawkins has never been good at following rules – even simple ones. And the recent grisly murder of a debtor, Captain Roberts, has brought further terror to the gaol. While the Captain’s beautiful widow cries for justice, the finger of suspicion points only one way: to the sly, enigmatic figure of Samuel Fleet.

Some call Fleet a devil, a man to avoid at all costs. But Tom Hawkins is sharing his cell. Soon, Tom’s choice is clear: get to the truth of the murder – or be the next to die.

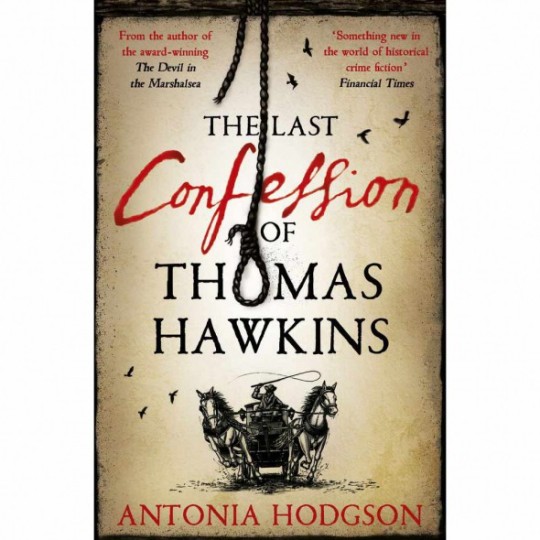

London, 1728. A young, well-dressed man is driven through streets of jeering onlookers to the gallows at Tyburn. They call him a murderer. But Tom Hawkins is innocent and somehow he has to prove it, before the rope squeezes the life out of him.

It is, of course, all his own fault. He was happy settling down with Kitty Sparks. He should never have told the most dangerous criminal in London that he was bored and looking for adventure. He should never have offered to help the king’s mistress. And most of all, he should never have trusted the witty, calculating Queen Caroline. She has promised him a royal pardon if he holds his tongue but then again, there is nothing more silent than a hanged man…

of posh ladies in big wigs and frocks. What we don’t see or hear much of is

the underbelly of C18th life, especially in classic costume dramas.

a) Why did you choose to focus on

this area of the period in your first novel, in particular?

I’m intrigued by neglected things, and the 1720s

and 30s are often skimmed over, especially in fiction. But every period in

history is momentous to the people who live in it. Street level stories can be

just as exciting and significant as the great mythic tales of warring monarchs.

I have nothing against writing about ‘posh ladies

in big wigs and frocks’, or fashion-conscious beaux, as long as it’s clear they

were a tiny fragment of the whole – the oligarchs, aristocrats and hedge fund

billionaires of their day. The vast majority of the populace lived on a knife

edge of debt, with one set of tatty clothes.

I’m also trying to reflect the preoccupations of

the time, in art and life. Think of Defoe’s Moll Flanders, or Hogarth’s

depictions of taverns and debtors’ prisons and madhouses. The most-performed

play of the eighteenth-century was The Beggar’s Opera, which had a

highwayman as its hero. Meanwhile 200,000 people watched Jack Sheppard hang at

Tyburn in 1724 – a third of London’s population.

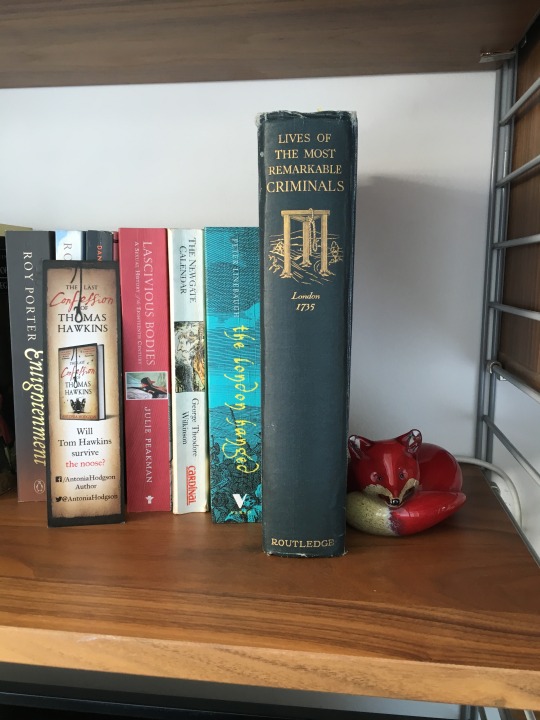

Some of the research texts consulted by Antonia.

b) In your second novel, we see the highest of

high society too. What did you enjoy about exploring the contrasts between

these two worlds?

After setting my first book in a prison over a

few short days, it felt natural to move out into the wider world. My

protagonist Tom Hawkins is unusual in that he can move easily between the court

of St James and the slums of St Giles. I enjoyed exploring the contrasts, but I

was also interested in the similarities. For example – how much freedom does a

queen have? Caroline of Ansbach – George II’s wife – was a bright, politically

astute, witty woman, but she was also constrained by her position and by her

husband. She had to scheme and make deals to get her way. Her role within the

novel isn’t so different from that of gang captain James Fleet, controlling

things through a mixture of sly intellect and menace from his den in St Giles.

“A shelf above my desk with select bibliography for Last Confession of Thomas Hawkins.”

[2] When I was researching for my C18th setnovel Song of the Sea Maid, I was often struck by the dichotomy of the ways in

which the C18th felt simultaneously alien and familiar to me. The weirdness of

everyone wearing wigs and stays and being carried around in chairs, next to the

familiarity of arguing about politics and reading the newspaper in coffee

houses, for example! Did you feel a similar way about the C18th?

Absolutely. I love reading a contemporary diary

or a letter and feeling a rush of familiarity. When I was researching my third

book I found a wonderful diary of a linen draper, written in 1728. There’s a

fantastic bit where he tries to get his friend drunk, comes out the ‘worse of

it’, vomits, collapses, wakes up with a crashing hangover and spends the next

day in bed, cringeing with shame.

*interrupts: Ha ha! I read the diary of a shopkeeper from the 1750s who kept going out with his mates and getting roaring drunk then he’d always write about it after and say what a terrible person he was and he’d never drink again and then he’d go and do it all over again the next night…*

One of my favourite discoveries was a note from

a little boy to his mother, tucked away in a parcel of letters in the West

Yorkshire archives. He thanks her for her letter, and says he kissed it ten

times. On the back of the note, his father has written ‘this is the first

letter Jacky wrote to his mama’. It’s such a tender thing. Of course we know

parents have always loved their children, but to hold something like that in

your hands three hundred years later is very moving. *interrupts again* Oh my! I love this so much!

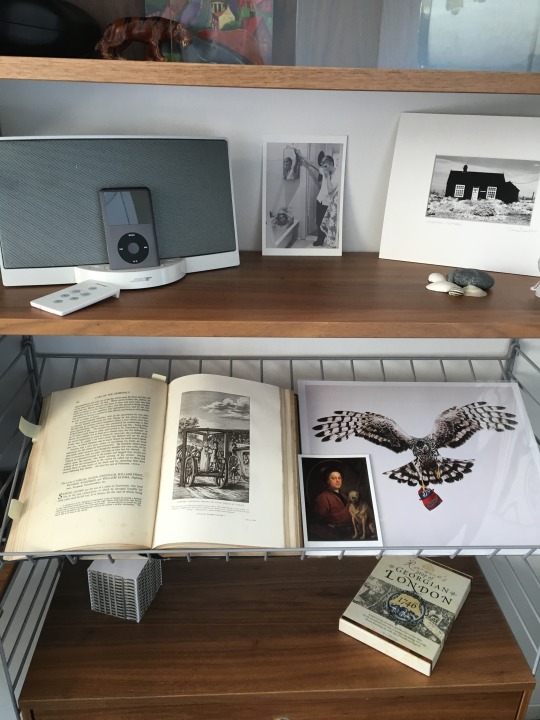

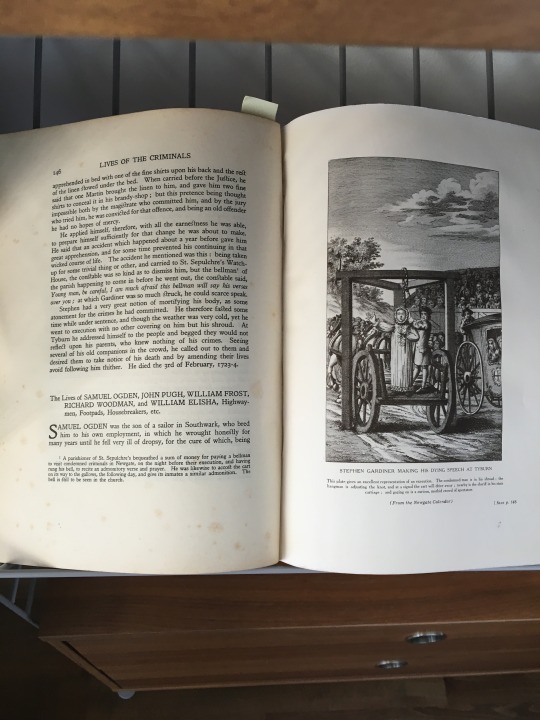

“This shows shelving to the side of my desk with The Lives of Remarkable Criminals opened out. This was one of the bestselling books of the era, and detailed the stories of condemned prisoners, including their dying words on the scaffold. The image shows a prisoner going to his death dressed in his shroud, to show he is a true penitent and ready for heaven. You can also see here a few tokens of inspiration – a picture of Hogarth, another of Bowie, a photograph of Derek Jarman’s cottage at Dungeness, some pebbles from a beach on the Isle of Harris.”

[3] Also, when researching I came across thehistory of the South Sea Bubble investment scandal and the devastating effect

it had on C18th society. Again I found myself making modern comparisons with

the subprime mortgage crisis and the recession. In what ways did you feel the

South Sea Bubble affected the characters’ lives in your novels?

I suppose all investment scandals and financial

collapses follow a pattern. Wilful optimism, greed, denial, disaster…! I think

it’s fascinating that those responsible for the collapse defended themselves in

a very familiar way, too. ‘Oh, if I’d tried to stop the scheme, it would have

collapsed even sooner.’ Or the old favourite, ‘everyone else was doing it!’

By 1727/28, you could argue that the terrible

harvests were causing more suffering than the South Sea Bubble. What remained,

eight years on – and what certainly connects with our modern experience – was a

huge suspicion of politicians. And they were right to be suspicious!

Visitors, I knew there would be a crime committed at some point in the

narrative, and though I wasn’t writing a crime novel per se, I did find a fantastic book about

crime fiction called ‘How to Write a Mystery’ by Larry Beinhart. As I

say, my crime story didn’t become a central part of my story, but I’m so glad I read that

book, as it taught me so much about plotting and enigma.

a)

Did you read up about crime

narratives? Were you influenced by any particular crime writers?

My biggest influence was Hogarth – the way he

moves from the gutter to the drawing room with such assurance. His unflinching

but compassionate gaze. His mix of wit and sincerity. His ability to capture a

range of characters with such ease.

I’ve always loved crime and historical novels,

so I’m sure I’ve absorbed all sorts of things from my favourite writers. I’ve

also worked as an editor for over twenty years, so have spent most of my adult

life thinking about pace, structure, character, voice. If anything, my main

concern when writing is to avoid over-thinking. I have to banish my inner

editor, at least for the first draft.

b) How did you plan out the crime aspects of

your narrative? Can you take us through some of your plotting techniques e.g.

timelines, post it notes, diagrams etc.?

It’s a combination of careful planning and

wilful abandonment. I write out all my ideas longhand – character sketches,

plot points, themes. I usually fill out a large notebook before I’m ready to

start. Then once I start writing, things evolve. I don’t stick rigidly to my

initial plot – in fact half the fun for me is playing around with it. So – a

mixture of planning and improvisation.

sites so useful in imagining past periods. I visited a working hop farm for The

Visitors and the Coram Foundling Museum for Song of the Sea Maid, amongst many

others. Can you share with us any travels you went on to research your C18th

books?

The great joy, of course, is visiting National

Trust properties and sampling their scones. That is the main reason we write

historical novels, isn’t it?

*interrupts: YES. And they do nice quiches.*

My first two books were set in London, where I

live. There’s nothing left of the first Marshalsea prison, but I would still walk

around Borough just to get a sense of the streets. (And in fact I used to work

there a billion years ago.)

My third novel is set up in Yorkshire, at

Studley Royal and Fountains Abbey. I’ve travelled up there countless times in

the last two years or so. I’ve seen it in every type of weather apart from

snow. The book is set in spring, so it was particularly useful to visit then in

terms of the wildlife, the flowers, the light, the sounds and scents. As with

all research, I find that I need a deep well to draw from, even if I only use a

thimbleful in the final book.

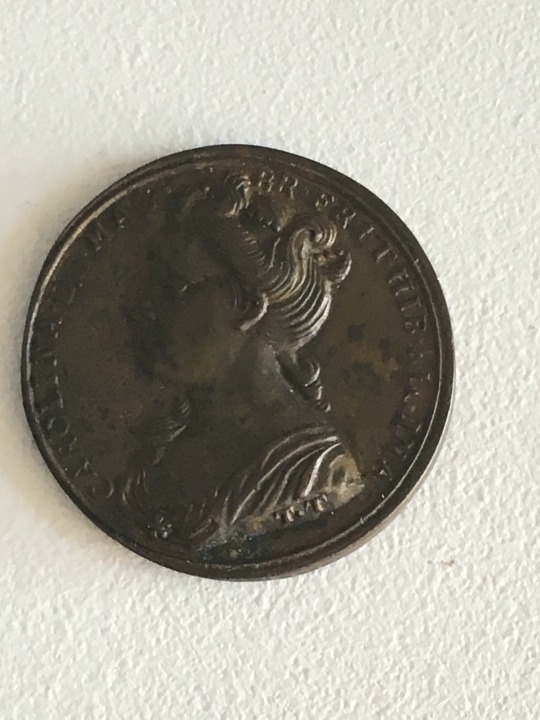

“This is a coin celebrating the coronation of Queen Caroline of Ansbach in October 1727. (She appears on both heads and tails.)”

[6] Anyone reading C18th novels nowadays willfind a wide range of C18th-isms in the layout and expression in the prose that

modern readers can find rather off-putting e.g. capital letters for most nouns,

using ’d for ed endings, italics for place names etc. In my own writing, I

chose to incorporate some aspects of C18th prose – such as the use of long

sentences and dashes – but to leave out the others. What kind of decisions did

you make about how to express the period in your prose without alienating your

modern reader?

In all honesty, I’m not sure I can describe the

process to you. I write in the first person, so it was all connected to

creating Tom’s character – how he would express himself. Beyond that, I suppose

my decisions came from reading a lot of primary sources and absorbing the

rhythms, the phrases. I don’t like to look back and analyse too much, as I’ve

got to the point where it feels instinctive, which I prefer. (Not that this is the

only way to do it of course – it just happens to work best for me.)

Fountains Abbey

[7] Can you share a little with us of what you’re working onnext?

My third novel is called A Death at Fountains

Abbey – it’s set up in Yorkshire. Deer parks, water gardens and terrible,

violent events. London can’t have all the fun.

Thanks so much to Antonia for sharing her thoughts on researching, working with and mentally living within one of my favourite periods in history. And I’ve been to Fountains Abbey and adored it, so I’m dying to read her new one!

You can find Antonia online here:

http://www.antoniahodgson.com/