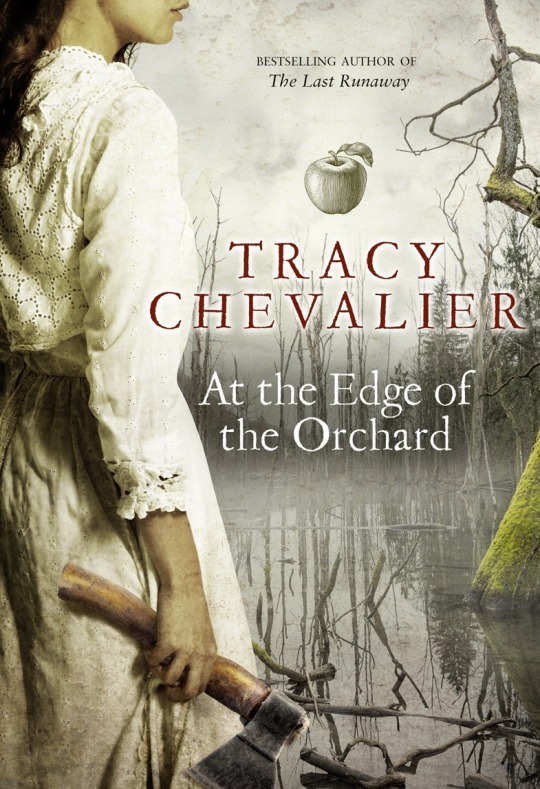

I’m delighted to provide the final stop on the Tracy Chevalier ‘At the Edge of the Orchard’ blog tour. I’ve been a fan of Tracy’s work since her debut ‘Girl With a Pearl Earring’ came out in 1999. As a fledgling novelist, I remember noticing how clever her metaphors and similes were, that they always used comparisons within the era, within Griet’s narrowed world view. I thought that was ever so clever and learned from it! I also learned a lot from the ways in which Tracy approaches historical fiction, in terms of weaving a story around a fascinating historical period, setting or topic, such as the case of apples trees in C19th America in her latest book.

Here’s the blurb:

The sweeping and compelling new novel from the bestselling author of Girl with a Pearl Earring.

‘Dark, brutal, moving, powerful’ Jane Harris

‘A wonderful book; rich, evocative, original. I loved it’ Joanne Harris

What happens when you can’t run any further from your past?

Ohio, 1838. James and Sadie Goodenough have settled in the Black Swamp, planting apple trees to claim the land as their own. Life is harsh in the swamp, and as fever picks off their children, husband and wife take solace in separate comforts. James patiently grows his sweet-tasting ‘eaters’ while Sadie gets drunk on applejack made fresh from ‘spitters’. Their fighting takes its toll on all of the Goodenoughs – a battle that will resonate over the years and across America.

Fifteen years later their youngest son, Robert, is drifting through Gold Rush California and haunted by the broken family he fled years earlier. Memories stick to him where mud once did. When he finds steady work for a plant collector, peace seems finally to be within reach. But the past is never really past, and one day Robert is forced to confront the brutal reason he left behind everything he loved.

In this rich, powerful story, Tracy Chevalier is at her imaginative best, bringing to life the urge to wrestle with our roots, however deep and tangled they may be.

http://www.keepers-nursery.co.uk/golden-pippin-apple-fruit-trees.aspx

Today I’ll be writing about some of the themes of the book and then Borough Press have kindly provided an extract from the book, which you can read at the end of this post.

Firstly, my thoughts on the novel. It is written in a bleak and beautiful, spare style.

Formidable research has been carried out, as ever with this industrious and

thorough author. I never knew how little I knew about apples until I read this

book!

The setting of the opening is oppressive and brilliantly

drawn – the Black Swamp of Ohio is not somewhere that springs to mind when I

imagined pioneers, which was a refreshing and new approach to the subject. It

also draws attention to the very real and deadly hardships faced by these people.

Little House on the Prairie it ain’t. This harsh, uncomprehending natural

American setting forms part of a trope in pioneer fiction, that the landscape

is unforgiving, at times menacing and at others utterly dismissive of the

petty fates of the people who crawl around on its surface. I’m reminded of the

vast landscapes of Annie Proulx, not in their flora and fauna which are very

different, yet in that sense that the land is not your friend, not your enemy

either, it is simply itself and pays you scant regard.

http://www.blackswamp.org/main/land-we-protect/

The story is told in an intriguing mixture of voices: 3rd

person, 1st person

dialect and letters. This technique provides an echo of the numberless voices

of the pioneers who fought and died unremembered to stake a claim in these

harsh environments. The range of characters includes real-life figures, such as

plant collector William Lobb and pioneer nurseryman John Chapman AKA Johnny

Appleseed. Now, I had heard of Johnny Appleseed but from a rather odd source: a

cartoon my daughter watched on DVD from the golden age of Disney cartoons,

called Melody Time. There was an animated version of the life of the man who

spread apple trees across the west. It was full of songs and cute woodland

creatures feeding from his hand, and so forth. Unsurprisingly, the reality was

quite different and Chevalier’s Chapman is a much more rough and ready chap

(and all the more interesting, of course).

This idea – of planting apple trees across America – is a

fascinating symbol as it achieves a kind of immortality for the cultivator. He

or she will die and return to the ground, yet the apple trees that were planted

will spread their seed and live forever, a horticultural echo of child-bearing.

Apples as a symbol are of course rich with associations – the most famous for

many being the symbolism of the mystical and forbidden fruit of the Bible – yet

also golden apples (as are the favoured Golden Pippin apples in this story) have

been a source of immortality in Greek and Norse mythology. James treats his

precious apples as a kind of treasure and a sweet nostalgia for his childhood,

which Sadie actively disdains and uses them for much more earthly pleasures

i.e. making some damned strong cider and getting roaring drunk. When their son

Robert escapes his toxic childhood and seeks his fortune beyond, what does he

look for but gold? Yet beyond his search for monetary wealth, he actually comes

across plant hunting as an alternative source of immortality, as the

magnificent Californian Redwoods he helps to cultivate may well live thousands

of years.

It’s a novel of complex imagery and yet told in an

accessible and stark style, exploring the search for immortality and a

connection to the natural world that perhaps we all have: the call of the wild,

the desire to make an impression on the landscape, the need for family and home.

Now, here’s an extract from the novel.

It’s taken from the second half of the book with Robert, now grown up and living in Goldrush California. It features the (real life) William Lobb explaining how seeds are collected and sent around the world and migrate just like people. It also links to the first half of the book with Robert asking William Lobb about the variety of apples his father used to harvest, so it encapsulates the integral theme of the book of how hard it is to break away from your roots no matter how far you run.

California

1853-1856

Robert spent the rest of the day collecting

cones while William Lobb took more notes and sketched

the trees. Lobb also gathered

branches, needles and bark, carefully preserving their structure. “These I’ll dose in camphor and send to Kew to be studied,”

he explained.

“‘Q,’” Robert repeated. “What’s that?”

“A botanical garden outside of London—the finest in the world. They collect

and study all sorts of trees and plants. I always instruct Veitch

to send them new discoveries. They’ll want to see the sequoias.”

Robert nodded,

trying to imagine

people interested enough in plants to study them. But then he thought

of his father grafting the apple trees, how methodical he had been, and it didn’t seem so strange.

They camped just beyond Calaveras Grove rather than near the

others—“so I don’t have to listen

to braggarts all night,” William Lobb muttered. After they’d eaten and were sitting

by the fire, Lobb smoking

a pipe, Robert shyly asked if he could look at the leather notebook the Englishman had been using all day. When Lobb handed it over he held it to the firelight and leafed through the many notes and the drawings of the Calaveras Grove sequoias. Overviews Lobb had done of a whole tree, sitting several hundred feet away in order to see it from several angles. Drawings of the trunk, the bark, several different branches, the needles, the cones, the habitat

under and around it. He had also sketched clumps of trees, and several sketches

that could be put together

into a panorama to give an idea of the size and scale of the whole grove. In some of the drawings

Lobb had included a small figure standing

next to the sequoia, wearing a hat similar to Robert’s own. He had never seen himself in a drawing, and though it was unsettling, he was pleased to be in William Lobb’s notebook.

There were also sketches of the cones,

as well as notes about their collecting: the date and location and elevation of where they had been picked up.

“What will you do with the seeds?” Robert asked, handing back the notebook.

“Send ’em to England.” Lobb stowed the notebook

away. “The English will go crazy for these trees. They already love the redwoods I’ve sent back, and lots of the California pines. These sequoias will be the kings of many an estate in Bedfordshire or Staffordshire or Hertfordshire—if they survive.”

“Is the weather the same?”

William Lobb snorted. “No! Plenty of rain, not much sun.

The redwoods seem to be doing all right, though: some of the seeds I collected a few years ago have been growing in England. But these—it’s dry here, with fires that pop the cones open so the seeds can get out. That will never happen in England. And it’s high up here—the beginning

of mountains such as England doesn’t have. It will be a gamble. But if they take …” He tossed a pinecone into the fire.

“What do the English do with the trees?” Robert persisted.

“Plant ’em on their property.”

“Don’t they have trees in England?”

William Lobb chuckled. “Of course. But they want new and different, you see. The wealthy landowners have been busy creating

‘tableaux’ on their grounds.”

At Robert’s blank look, he added, “They lay out trees so they look like works of art rather than just letting nature grow as it will. Now they’re demanding conifers,

for they love exotic trees that remain

green all year round. They set off the broadleaf trees,

with their changing

colors, and provide structure and life when everything else is bare. There are few native conifers there—only the Scots pine, the yew, the juniper. So I’ve been sending as many as I can from California. Some of them are even creating

‘pinetums’ on their property where they plant and show off a variety of conifers.”

“You send trees to England.” A thought was stirring deep in Robert’s mind, like a fish swimming below the surface of a lake.

“Yes, saplings

sometimes, though they often don’t survive the journey. Seedlings are better—being smaller they don’t snap off so easily. But you may as well send seeds,

that’s best. Even then, many seeds never grow. You might plant a hundred and get twenty seedlings from them, and of those, five might grow into saplings,

and two into trees.

That’s why I have to collect

so many cones—as many as

my

horse can carry. Your horse too, if you’ve the time to ride to San Francisco. I assume you do or you wouldn’t be out here just to look at trees.”

It took Robert a moment to understand William Lobb was asking him to work for him for longer than just that day. Before he could answer, Lobb added, “I’ll pay you, of course. It’s worth my while to be able to collect and carry twice as many cones.” Clearly he’d thought Robert’s hesitation was over money.

Actually Robert would have helped him for nothing. He had been hesitating because the thought was now surfacing. “Have you ever heard of a Golden Pippin?” he asked.

“Of course.” William Lobb had finished his pipe and was taking off his boots. He seemed unbothered by the swerve in conversation. “I’m more of a Cornish

Gilliflower man myself, though. I prefer my apples with a bit of red on ’em.”

“Are Golden Pippins common in England, then?” Robert tried to hide his disappointment. From the way his father had talked,

he’d always assumed that Golden Pippins were very rare, known only to the Goodenoughs.

“Common enough. Not as common as a Ribston

Pippin or a Blenheim Orange, but easily found. You know George Washington had them brought over to Mount Vernon?

They didn’t thrive, though—not the right climate.”

“The Goodenoughs’ trees did.”

“Did what?”

“Thrive. We grew Golden

Pippins in Ohio, and Connecticut before that. My grandparents brought branches

from England and grafted them, then my father did the same when he went

to Ohio.”

“Really?” For the first

time, William Lobb looked

at Robert with genuine interest. “Your father was a grafter, was he?”

Robert nodded.

“My brother and I used to do a bit of grafting at Killerton, back in Devonshire. What was the yield of yours?”

“Ten bushels a tree.” Robert allowed himself to think about the Golden Pippins for the first time in years. “Have you ever tasted a pineapple?”

“Pineapple?”

William Lobb chuckled. “I ate them

every day in South America. Got

tired of

them. Why?”

“That’s

what our Golden Pippins tasted of: first nuts and honey, then pineapple. That’s how Pa described it, anyway. I never tasted real pineapple. Not sure he did either.”

William Lobb was staring at him.“Where did the Goodenoughs come from in England?”

Robert frowned. He wanted to say he couldn’t remember, but he knew that was not an acceptable

answer to someone like William Lobb. He tried to think of what his father had said, so long ago. “Herefordshire,” he dug out at last.

Lobb suddenly laughed, a great bark, almost

a shout. “Pitmaston Pineapple,” he announced.

Robert raised his eyebrows.

“Pitmaston Pineapple,” William Lobb repeated.

“That’s what your father grew. It was a Golden Pippin seedling that originally grew in Herefordshire, had an unusual

taste and a local following. Several years ago a man growing it in Pitmaston exhibited

it at the London Horticultural Society. Gave it the name ‘Pitmaston

Pineapple’ because of the pineapple finish. I’ve read about it but never had one. Been out of England too much to keep up with apples.”

“I didn’t know apples could change their taste.”

“Well, they go from sour to sweet sometimes.”

“I know. One in ten seedlings turns out sweet.” Robert repeated his father’s words.

William Lobb nodded,

pleased. “If they can change from sour to sweet, there’s no reason why other tastes can’t change: from lemon to pineapple, for instance.”

He pulled a blanket from his bag.

“So an English tree has come to America,” Robert spoke his thoughts aloud, “and now you are sending American trees to England.”

“True. There is a commerce in trees, just as in people. But a Pitmaston

Pineapple growing in Ohio?”

William Lobb chuckled, wrapping his blanket around him in preparation for sleep. “That’s almost enough

to make me go there, just to taste it!”

—————————————

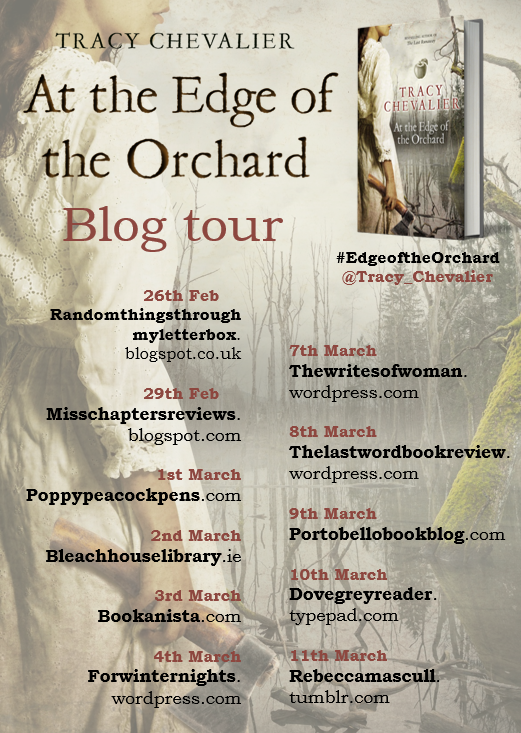

You can catch up with the rest of the Tracy Chevalier blog tour by clicking on the links below:

Thanks to Hayley Camis and Borough Press for the invitation to take part in this super blog tour. 🙂