I’m seriously star-struck today, folks, as the Rt Hon Alan

Johnson MP is visiting the blog to talk about the first volume of his memoirs,

THIS BOY, winner of the Orwell and Ondaatje prizes. It’s a beautiful book –

honest and true, yet never commonplace; shocking in its depiction of 1950s

poverty yet the opposite of maudlin. I’m thrilled that Alan took time out of

his crammed schedule to answer some questions for me about the book.

importance of books to you. In your early years, you owned Robinson Crusoe and

Tom Sawyer, and your sister owned Little Women, all of which you read

voraciously, later coming across Geoffrey Household too. What influence do you

think these particular books had upon you as a reader, writer and as a person?

“settling down with my book in the little back room, pulling the armchair close to the fire”.

These books were very important to us because, unlike the

library books we’d always had ever since our mother took us to Ladbroke Grove

Library when we were very small, they didn’t have to be returned; they formed

our own library. They also happened to be very good books which I read

and re-read but, as I say in the book, it was ‘Shane’ by Jack Schaefer that

became a book I was even more obsessed with. As a writer, the way that

book is structured, drawing the reader in from the first page when Bob

Starrett, a boy of my own age at the time, sees Shane in the distance and

follows his progress towards the ranch … as a person, I wanted to be Shane

rather than Bob Starrett, and it’s not an exaggeration to say that books such

as this taught youngsters like me the difference between being good and being

bad.

Alan was disappointed with the film version, that Alan Ladd was too fair-haired and friendly, not dark and brooding as the real Shane in the novel.

[2] At the Cox family’s home, your dear friends when youwere growing up, you coveted the copies of Dickens in the locked book case.

Later, Albert Cox’s kind gesture meant you could borrow David Copperfield,

which meant a lot to you as a boy. Did you identify with David’s plight (which

of course echoes young Charles’s experience in the blacking factory)? And which

are your three favourite Dickens novels and why?

‘David Copperfield’ is quite definitely my favourite

Dickens’ novel. I don’t think I identified with the lead character, but

reading it over that 12-month period after my mother’s death did provide escape

and, I suppose, comfort. As for the other two favourite Dickens’ novels,

it’s a difficult choice but, if pushed, I would choose ‘Bleak House’, because

of the amazing Inspector Bucket, and ‘Great Expectations’, which is the perfect

novel.

in the book. Did you walk again down those old streets, to reacquaint yourself

with the places you would roam as a boy? If so, what emotions and thoughts did

you experience during these walks? (By the way, this reminds me of one of my

all-time favourite quotes – “He was of the streets streety.”)

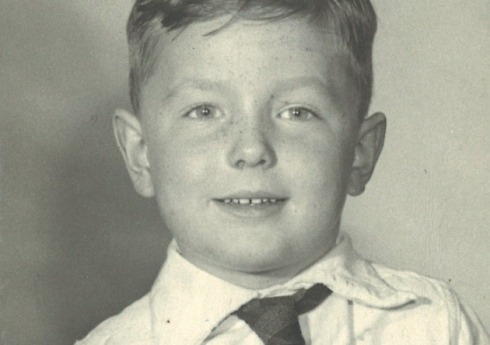

Cheeky chappy: Alan at 8 years old.

I’ve walked down those streets twice since I left

them. The first time was during summer Recess before I became a Minister,

when I had a bit of time on my hands and decided to go to see my son, who was

working in a recording studio in Kilburn, via a long walk from Ladbroke Grove

Station along Golborne Road, down Southam Street, and eventually up the

Ha’penny Steps. At that time (1998), I hadn’t even thought about writing

about my youth. I was bemused by the building developments which stopped

me going down familiar streets that either didn’t exist any more or were blocked

by a row of houses. I remember thinking at the time the only thing that

had changed was the architecture. However, when I went there for the

second time, with my sister when she came over from Australia in 2012 and the

book was very much on my mind, we turned the corner off Golborne Road to see

that roughly where we used to live at 107 Southam Street was now artists’

studios, and parked outside was a Bentley. In other words, it had changed

a lot.

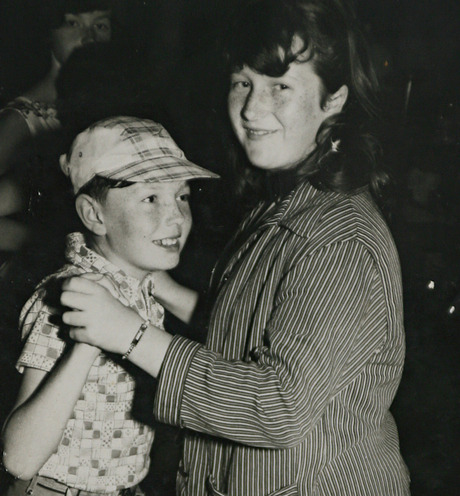

Alan and his sister Linda: “who kept me safe”.

[4] Near the end of THIS BOY, you mention “yourincreasing loneliness” and I had the impression that this was the first

time you’d actually mentioned feeling lonely. This goes with the honest yet never mawkish style in which

you write, never a hint of ‘poor me’. But did you perhaps suffer from

loneliness more than you describe here? If so, I’m imagining that your later

career as a politician, where you are surrounded by people from dawn till dusk,

would have been a cure for any loneliness. And now you’re an author too, a

solitary profession (when writing). Do you value that quiet time when you’re

writing and how does that balance with your very public role the rest of the

time?

This boy: Alan, aged 5.

I can’t tell you how much I enjoy the solitary nature of

writing. I am, by nature, a loner, and the reference to my increasing

loneliness was describing a time when I left the home of the Cox family, where

there was always something happening, people coming and going, and where we all

sat on a Saturday night to watch the midnight movie on BBC2, to go and live in

a rented room in Hamlet Gardens in Hammersmith, where Mrs Kenny, the landlady,

rarely appeared and we led separate lives. I found the contrast

difficult, but I think the main problem was that, unlike my best friend Andrew,

I didn’t have a girlfriend.

Alan aged 18 on his wedding day with new wife Judy and sister Linda.

[5] You describe one of your first jobs at Tesco as a timewhen you started to consider the issue of workers’ rights and how to protect

them. Was this the beginning of your political consciousness or did that come

earlier, in your sister’s dealings with the authorities, and the way your

mother was treated by the system in which you all lived?

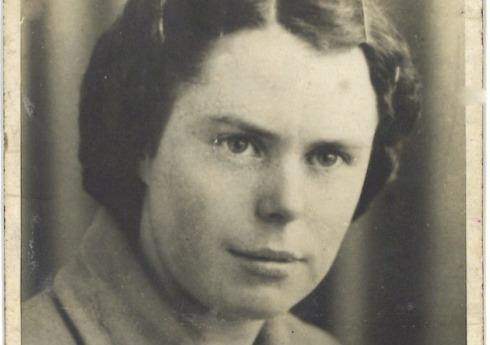

Alan’s mother Lily as a teenager, when she was working for the Co-op in Liverpool: “only Linda and I knew the true extent of Lily’s heroic attempts to overcome adversity”.

I don’t think there was a single epiphany in terms of my

interest in workers’ rights. Certainly my treatment at Tesco rankled with

me, not so much the incident that got me sacked (although I still maintain that

I resigned!), but the fact that they promoted me to Warehouse Manager without

letting me wear the natty, cream linen jacket that was the apparel of all substantive

managers. All my other experiences just went into the swirl of emotions

that eventually made me decide that I was on the left of the political

spectrum.

the best of the best), you’ve said that after the third volume of your memoirs,

you’d like to write fiction next. Will you be leaning more towards Dickens or

Household, or a mixture of both?! And what other literary influences might

inspire you?

I’d love to write fiction if my publisher will indulge me,

and after the next volume of memoirs I hope to get a chance. I have a

very clear idea of how I want to write, but I wouldn’t describe it as being a

nod towards either Dickens or Household, or even Jack Schaefer. I love

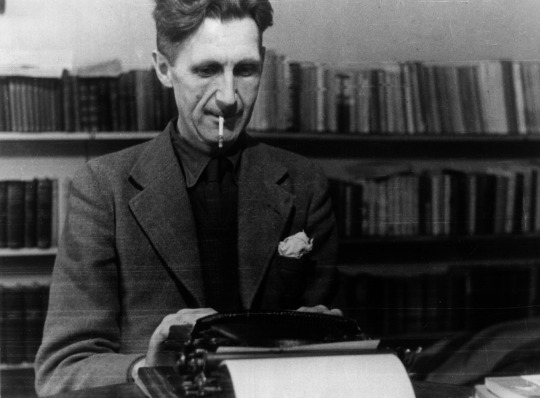

Hardy, Trollope, A S Byatt, Elizabeth Taylor, George Orwell, Nabokov, Pullman,

etc, etc. If a fraction of their genius finds its way into a sentence

that will be wonderful. I want to write an historical novel, and if I can

complete the plot I hope I’ll be able to find the words.

George Orwell

I’ll bet you a tenner his publisher will indulge him…They’d

be nuts not to! A huge thanks to Alan for sharing his thoughts here.

The second

volume of his memoirs – PLEASE MISTER POSTMAN – is out now from Transworld:

http://www.transworldbooks.co.uk/editions/please-mister-postman/9780552170659

with a third volume to come soon (and then an historical

novel, with any luck. I wonder what era he’ll choose?)

You can find Alan online just about everywhere (and on TV

and the radio just about every day at the minute), yet here are some useful

links:

http://www.transworldbooks.co.uk/authors/alan-johnson

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b06g5g5f/alan-johnson-the-post-office-and-me

Alan Johnson MP