Such an honour today to welcome to the blog the Australian author – and a writing hero of mine – Kate Grenville. I read THE LIEUTENANT when it came out and was captivated. I knew immediately that this was a writer who could write anything she liked and that the reader would always be in the safest pair of hands. Beautiful, poetic prose and compelling plots, along with a deep understanding of human nature, all make Kate Grenville one of the top novelists at work today, I’d argue. She’s recently turned to family history to write her latest book: ONE LIFE, which tells the story of her mother’s life.

Here’s the blurb:

One Life is the story of Nance Russell, whose life spanned a century of tumult and change. In an act of great imaginative sympathy, her daughter Kate Grenville has drawn on the fragments of memoir Nance left, to create an intimate account of the patterns in her mother’s life.

In many ways Nance’s story echoes that of many mothers and grandmothers, for whom the spectacular shifts of the twentieth century offered a path to new freedoms and choices. In other ways Nance was exceptional. In an era when women were expected to have no ambitions beyond the domestic, she ran successful businesses as a registered pharmacist, laid the bricks for the family home, and discovered her husband’s secret life as a revolutionary.

One Life is a deeply moving homage by one of Australia’s finest writers.

love and regard you have for your mum:

“What a great gift it was to have had her for a mother…Why

does a person become a writer? I owe so much to my mother. She read to me when

I was a child, made it clear how much literature mattered, told me the family

stories that, years later, inspired the books I’m most proud of having

written.”

What was the impetus to write about your mother’s life?

And what surprised you most in the writing of her story?

The impetus to write about my mother’s life came from her ,

and the many fragments of memoir she left me.

She knew her story was worth

telling – not because she thought she was anyone particularly ‘special’ in the

sense of being rich or famous – but because her story was typical of so many

women of her generation. She was born in

1912 and died ninety years later, so she lived through the incredible changes

of the twentieth century. It was a time

of change of kinds the world had never seen before – for everyone, but

especially for women, and especially women like her, born without any

privileges of money or position. She was

a pioneer who took advantage of all those changes.

In an era when women were supposed to want nothing more than

to keep house and look after the children, my mother ( the daughter of a

shearer turned pub-keeper) trained as a pharmacist, started her own successful

pharmacy businesses, married a Trotskyite revolutionary, laid the bricks and

nailed the floorboards for the family home, and in her fifties went back to

university for the education she’d always wanted. In between all that she brought up three

children with (especially at the start) never enough money.

What surprised me most in the writing was the texture and

detail of daily life in a time that’s so recent and yet almost

unimaginable. She told the story of all

the women in the street crowding into someone’s laundry to watch the new

unbelievable miracle of the washing machine – this was 1946, just a few years

before I was born. I asked her once

what she thought of herbalism – thinking that, as a professional pharmacist, she

might be sceptical about it – and she told me that when she was training in the

1930s, pharmacists WERE herbalists, because modern medicines like antibiotics

hadn’t been invented, so herbs and minerals were all pharmacists could use. Contraception

was unbelievably primitive and ineffectual – a bit of sponge on a string soaked

in vinegar was about the most sophisticated thing a woman could use. The

world Mum grew up in seemed incredibly ancient , and yet it was only the

generation before mine.

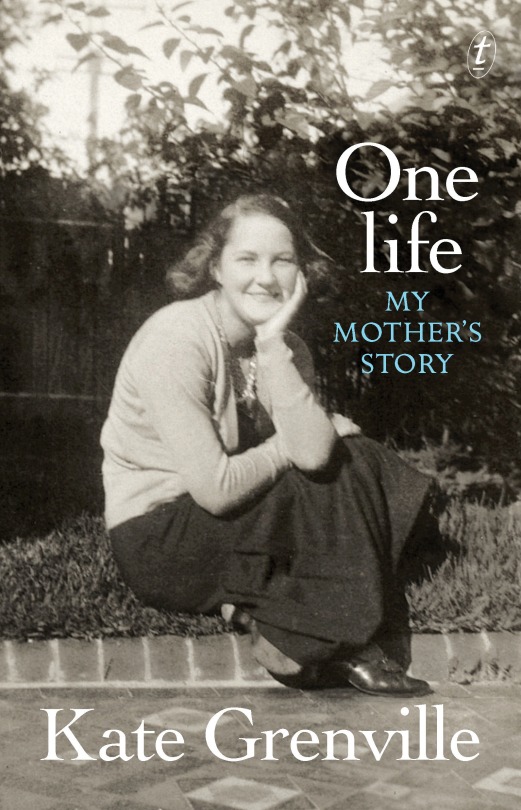

Kate Grenville’s mother, Nance.

[2] I’ve loved

reading your novels and now this special family biography. Your prose is

stunning and I do believe you could write about any old thing and make it sing.

For example: “the still pool with trees hanging over the

bank where a platypus rippled along the surface at dusk, and the place at the

end of the pool where the water mumbled over the rocks.”

I’m interested in how you achieve this loveliness through

your drafting process. Do you write quickly and tinker afterwards? Or do you

pore over poetic passages as you go, slowing your writing right down?

My motto in writing is “Fix it up later”. I don’t go back until I’ve got most of the

story down, no matter how clunkily. For me, writing is a matter of momentum –

like riding a bike – stop and you fall off.

There’s an energy generated when you just keep going without going back

and without planning it all too much – freewriting if you like to call it

that. In among the energy there’s plenty

of rubbish, but there’s always something

that’s strong and full of life.

As a reader, I love to be surprised – and as a writer I love to be

surprised too and that doesn’t happen if you plan too tightly. Once the story

has blurted itself out in its main elements, then it’s time to go back and

winnow out the rubbish. After all, until you have an idea of what the story is

trying to be, it’s hard to know what’s rubbish and what’s treasure.

The other thing I cling to in writing is the idea that if I

don’t know it ( or know something like it), I don’t write it. That sentence you quote – there’s a

particular stretch of river I know, that I drew on for it. As I wrote, I could remember the platypus

just breaking the surface as it swam, I could remember the sound of the water

over the rocks, the particular smell of an inland river … without that physical

familiarity it’s difficult to convey it vividly to a reader. (Of course there’s nothing wrong with

shifting the reality a bit – the river I had in mind is actually about three

hundred miles away from the one I was writing about, but I didn’t think anyone

would mind. Many things can be forgiven

in fiction, but being boring isn’t one of them.)

even more so – injustice. Your mother seems to have felt that too. How was this

imparted to you when you were growing up and a fledgling writer?

I was very lucky to have two parents who thought deeply

about matters of justice in human affairs.

My father was a Trotskyite (a kind of communist) before and during world

war two, and my mother was politicised by the hard lives she saw around

her. She often talked about people who

were intelligent but hadn’t had the opportunity of education and saw how wrong

it was that people missed out. Her own parents’ education had only gone as far

the end of primary school because they came from poor families. She could see how frustrated her mother was –

she was a clever woman who’d wanted to be a schoolteacher – and how lack of

education had given her father no judgement in making decisions about his life.

Mum had no time for social pretension or for people who thought they were

superior because of the accident of having been born into the right sort of

family.

Kate’s mother and father – Ken and Nance – with baby Christopher in 1941.

She taught us those values in very concrete ways. When I was seven or eight, a man came to the

door selling some very feeble doll’s-house furniture – he was a sadsack sort of

older man and the things he was selling were made from toilet-paper rolls and

matchboxes. Mum invited him in, made him

a cup of tea and chatted with him, and bought most of what he was selling. I made no secret of my scorn at these rather

pathetic things, and she gave me what was for her quite a sharp lecture: he was

a poor old man struggling to get by, she

said, and it was the duty of people who had advantages – like us – to respect

and help such people. I remember it very

vividly because once she’d explained it, I was deeply ashamed.

*interrupts – ‘sadsack’ is now my word of the day…* 😀

sadsack

noun

an inept blundering person.

[4] I loved this partwhere your mother realises the power of literature:

“a spilling crowd of faceless and voiceless people, all

bound together by having their feelings put into words. Standing in the dusk

watching the great yellow eye of the tram light rushing towards her, she

understood why some words were worth binding in leather and handing on.”

Which novels or poems have made you feel less alone on this

earth?

Shakespeare always gives that little shiver-up-the-spine of

Yes, that’s just how it is. In a different way, the Bible does too ( I’m not

religious, but the Bible is full of stories of very recognisable human beings

acting out of their flaws and hopes and fears).

The lovely musical poetry of the nineteenth century does it for me

(Keats, Wordsworth, Hopkins) and so do the novels of Woolf, de Lillo, Taylor,

Greene and of course the great Australian humanist Patrick White.

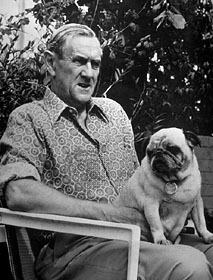

Nobel Prize-winning novelist Patrick White (and friend).

Mum felt that literature, read the right way, could be a

kind of instruction manual for life, and she’s passed that idea on to me. I do enjoy a good beach read ( I love John le

Carre’s novels) but the books I really treasure are ones with a moral dilemma

at their heart , and complicated human beings working through the puzzles that

life presents them with.

A huge and grateful thanks to Kate Grenville for taking time out of her busy schedule to answer my questions. I think I’ve just found one of my favourite maxims for writing, when Kate said:

“Many things can be forgiven in fiction, but being boring isn’t one of them.”

Love that.

You can find Kate online here: