I’m honoured today that the wonderful novelist Valerie Martin joins me on the blog to discuss her latest novel THE GHOST OF THE MARY CELESTE.

I read Valerie’s brilliant novel PROPERTY when it first came out and was hugely impressed. So I was very much looking forward to reading her latest and my word, I was in no way disappointed. In fact, it was one of the best novels I’ve read in a long, long time. It is complex, it is ambitious, it is not an easy, breezy read, yet it draws the reader in and weaves a world around you. It deals with grief, love, truth and belief, and is supported throughout by impeccable historical research into the Victorian period, Conan Doyle, shipping and spiritualists and so much more.

So, I’m thrilled that Valerie very kindly agreed to answering some questions for me and her responses are as detailed and fascinating as her novels.

[1] The ghost ship as a symbol is a powerful one, lost andlonely, doomed to wander the oceans forever. It haunts the characters as an

image of everything they have lost. It is a mystery, as is the veracity of

spiritualism and, beyond this, death itself. How did you come across the legend

of the Marie Celeste and what drew you to it as the subject for a novel?

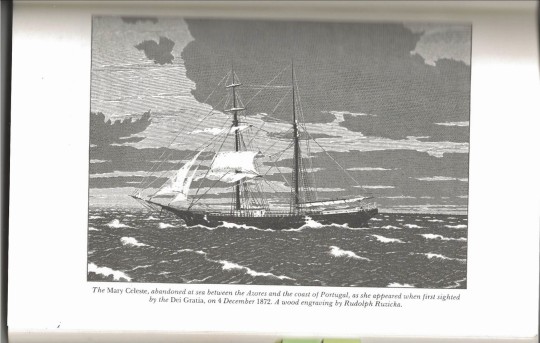

Yes, the image of an empty ship drifting aimlessly, as the Mary Celeste was in 1872 when she was sighted by

the first mate of the salvage ship the Dei

Gratia,

seems to come out of the unconscious.

Most accounts I read of the mystery begin with the description of this

sighting, the sense the mate had, even from a distance, that something was

amiss, that this ship was unattended.

Unmanned ships cast adrift weren’t that uncommon in the 19th century,

but the reason for their abandonment was usually clear. The Mary Celeste was certainly a spooky sight, but the

mystery was why the crew wasn’t on her. The ship

was

in good condition; she was boarded, crewed, and sailed to Gibraltar for a

salvage trial that became international news.

I first read about the Mary

Celeste in

a journal called The Weekly Reader, a children’s

newspaper issued to the public schools in New Orleans. The article sketched the events, and there

was a picture of a sailing ship, which interested me because my father was a

sea captain. I spoke to him about the Mary

Celeste,

and though he had heard of it, he had nothing to add to the story. His vessel

was a huge cargo-passenger behemoth and he was not much interested in

sailing.

I didn’t think about the story for many years until by

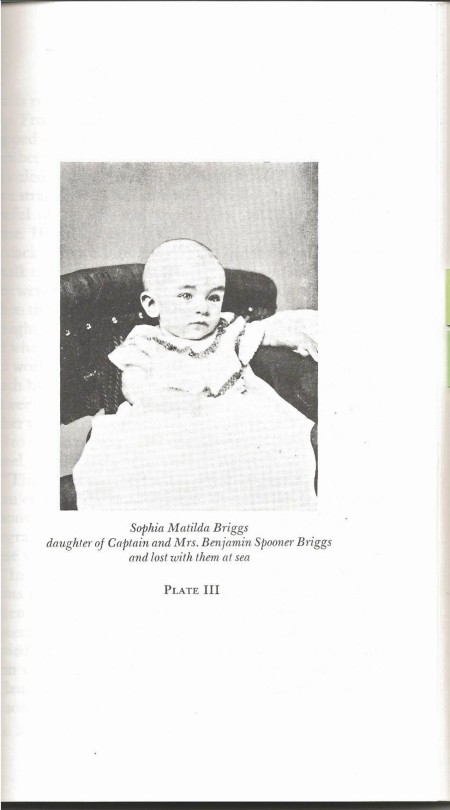

chance – and I don’t remember where – I read a detail that surprised me: Benjamin Briggs, the captain, had his wife and two year old daughter

aboard. It wasn’t just another tale of

men lost at sea, there was a family attached, both on the ship and at home. A little research opened a door into an

unexpected world close to home. The Briggs

family hailed from Marion,

Massachusetts, a town entirely run by cantankerous sea captains, about a three

hour drive from my house in New York.

of life on board ship in the 19th century.

What aspects of your research did you find most useful in bringing this

precarious existence to life for you? And what personal connections do you have

with the sea?

I’m horrified by the sea and I think more people should

join me in this rational view. I enjoy

walking on the shore and maybe a wade to the knees, but that is it. Boats and ships terrify me: I avoid them at all costs. I have occasionally taken ferry rides that

weren’t entirely fraught with fear but for the most part every moment I spend

in a watercraft is three parts anxiety to one part wonder at finding myself

there. That opening chapter was the

result of weeks of exhausting research, trying to remember nautical terms and

get my brain around the contrariness of the terminology – lines are called

sheets and sails are shortened, made, or set, when water comes over the side,

one says “she shipped a sea.” I know nothing about sailing. The best help came,

as always, from letters and memoirs. A

lot of women went to sea and they wrote about it. Hattie Atwood’s memoir of a

trip around the world she made with her father when she was sixteen (he was the

captain) was helpful, as was THE MAKING OF A SAILOR, by Frederick Harlow, and

of course Joseph Conrad’s weird and authoritative memoir THE MIRROR OF THE

SEA. A book titled HEN FRIGATES (the term used by sailors to describe a ship

with the master’s wife or children aboard) really gave me a sense of how

claustrophobic life at sea was. I don’t

think most marriages today could stand up to the enforced intimacy of a 19th

century voyage spent with one’s husband and child in the captain’s narrow

quarters.

So I read a lot and worked very hard, wrote that opening

chapter, which describes a real disaster at sea – a sailing ship plowed into by

a steamer off the coast of Cape Fear ( Benjamin Brigg’s sister died in that

accident), and sent it to a colleague at

my college who knows a great deal about sailing and takes students out on long

voyages aboard big 19th century ships every year. He sent my pages back just covered with

corrections. I’d got about 80 percent of

the terminology dead wrong. That was

when I thought I might just give up on the project.

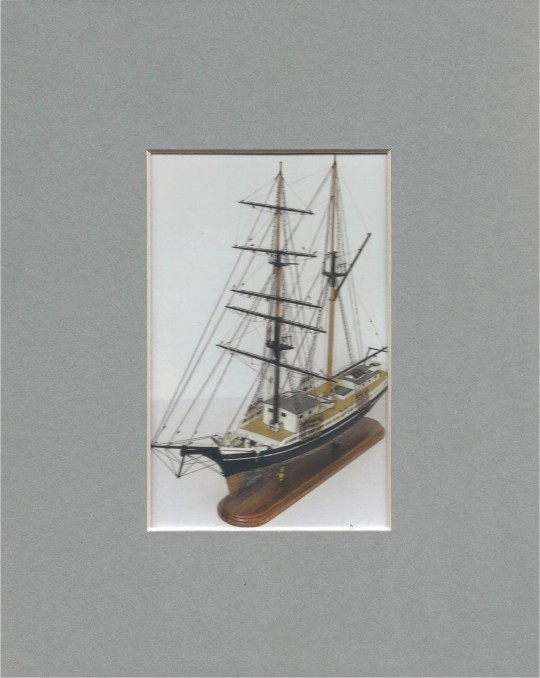

My lived experience was a visit to a museum ship, the Peking , which is anchored at South Street

Seaport in Manhattan, and an evening cruise in a small two-masted mail schooner

out of Key West. The crew served wine

and cheese and a sailor sang chanteys.

It was chilly, the water was a little choppy, it was obvious that if you

didn’t hold on to something you could slide right into the drink. Two hours of horror.

seekers of the truth e.g. Phoebe Grant, the journalist; Conan Doyle, a medical

man; even Violet Petra, the psychic is engaged ostensibly in the same pursuit.

Was that a theme you were interested in pursuing in this novel?

Ah truth. Like

beauty it exists in the eye of the beholder.

Nobody has any problem with the notion that what is beautiful to one

person is not to another, but the suggestion that truth is equally dependent on

subjective apprehension gives everyone the jitters. Truth and beauty, as the urn told John Keats,

are twins. Everyone agrees that beauty

is fleeting, why not truth? Like beauty,

truth degrades with time.

You’re right to observe that my characters are after

something they might call the truth. Phoebe Grant, a journalist, and Conan

Doyle, an eye doctor, would like to believe they can determine the truth by

looking at the facts. Violet Petra has

stumbled upon a truth that overrides all others: people will believe anything.

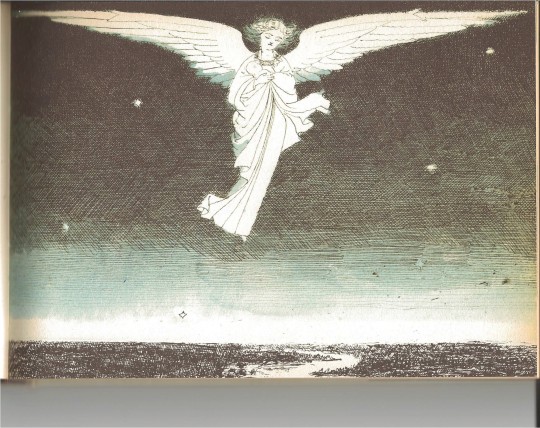

An image from Charles Doyle’s sketchbook, Arthur Conan Doyle’s father, painted whilst in the asylum.

It’s hard to say what I was pursuing in this novel. I began, like Phoebe, as something of an

innocent, curious and skeptical, hoping to give my readers a good story without

closing down on one version, as it was

clear from the start that the Mary

Celeste

has accrued a lot of barnacles over the years and also that it is not possible

to know what really happened. But the

deeper I got into the research the more insistently certain elements tangential

to the actual events clamoured to be included.

Each of the characters you mention has something to hide, a secret from

the past that they don’t want disclosed, so in a way, the truth is dangerous to

them. Phoebe is the most honest, but

she’s running from her nightmare childhood, Violet has an entirely new identity

to protect, and Conan Doyle is guarding

the secret that his incurably alcoholic and insane father was locked

away in an insane asylum for most of his adult life.

shot through with a delicious sense of humour! Love and sex scenes are so

tricky to get right – did you plan it this way or did it just come out that way

in the writing of it?

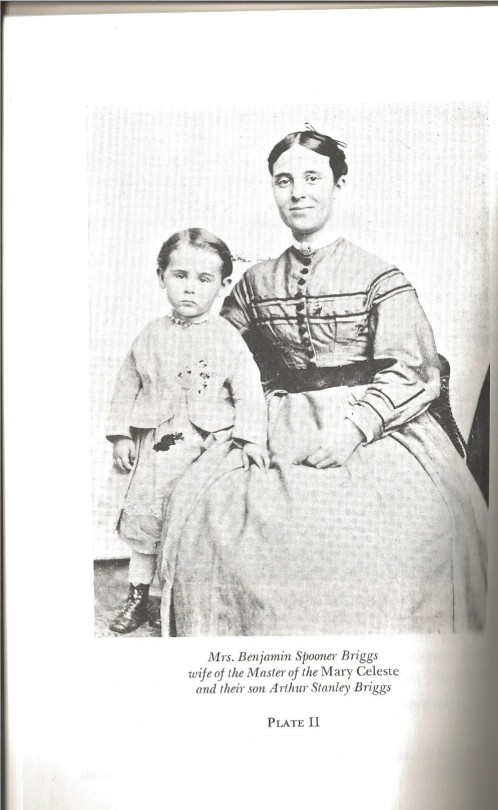

Sarah Briggs was the daughter of

a preacher, Leander Cobb, known for his thunderous orations in the “western”

style. She married her first cousin,

Benjamin Briggs, ten years her senior.

For several years when they were children the Briggs and the Cobbs all

lived in the parsonage in Marion on Buzzards Bay, so Sarah was marrying a man

who had been nearly a big brother to her most of her life. This was no

nightmare wedding night between two strangers! They were both raised by

seriously religious parents but in her letters Sarah sometimes alludes

caustically to religious matters and

Benjamin was described by all who knew him as possessing a lively sense of

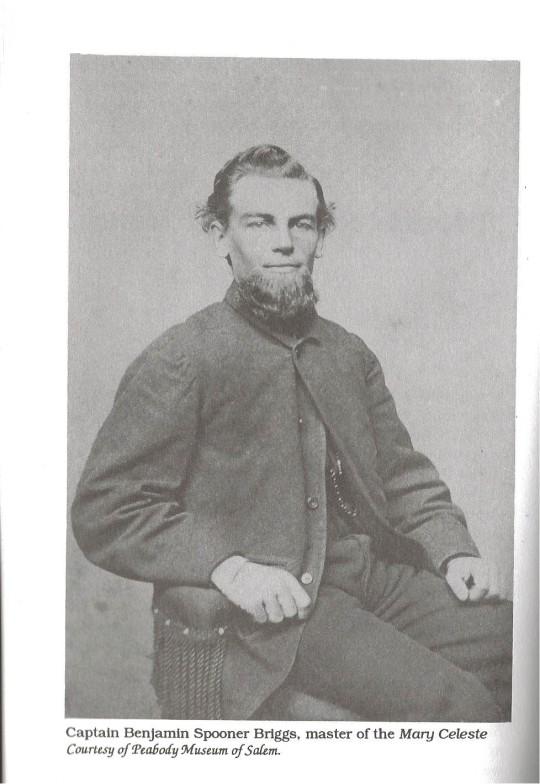

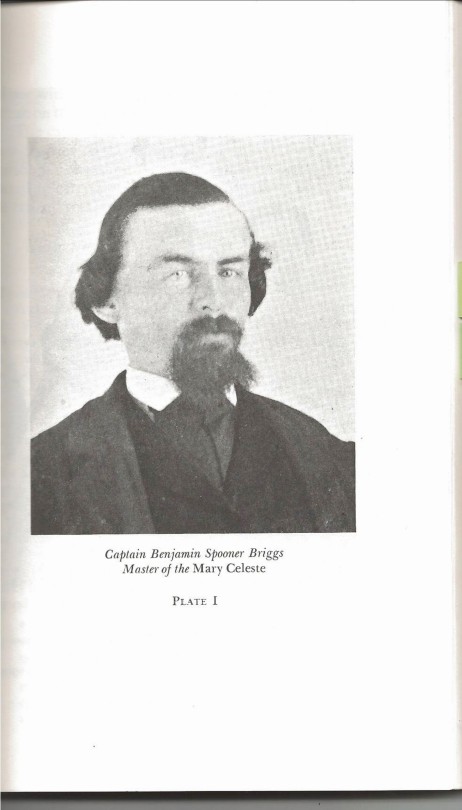

humor. You can see it in his smile in this photo.

Benjamin was

teetotal and was known to read a chapter

of the bible every night of his life. I

got down my bible – a book I seldom read – and began to follow Benjamin’s practice. (Not the teetotal part). I dislike reading the bible, so this wasn’t

easy, but I persevered. Soon I began to

jot down passages that a mischievous man, thinking of his coming wedding night,

might chuckle at while reading. When I

hit “look not every man on his own things but every man also on the things of

others,” I knew that would break Sarah up.

And his whispered command as they stand at last naked and ready for

their first night together, “Let love be without dissimulation,” must surely

amuse and endear him to her forever.

beautiful; for example, “I made out the train, like a drop of ink spreading on

a page, far down the track.” Do you pause in the progress of your writing to

work on poetry like this or is it generally something that comes later, in the

editing stage? How does your drafting process work.

I’m a plodder and a pauser. I write by hand and try never to leave blanks

that I plan to get back to. 250 to 500 words a day is a good pace for me. I consider myself very poor at metaphors but

sometimes they come to me with not much effort; the one you site is one of

those. I stop and think “what is it

like?” over and over, get up, walk

around, get another cup of tea, consult a thesaurus, draw a picture of whatever

it is in the margin, discard the many tired images that arise – It’s like a

gathering cloud, it’s like a black horse moving fast, it’s like an explosion of

ants – until something decent comes along.

her from a range of other points of view, as well as her own, which really

deepens our understanding of her. She has such a fascinating, scene-stealing

presence in the novel, were you ever tempted to make her the narrator and

centre of the story from the beginning?

Another image from Charles Doyle’s sketchbook.

I didn’t intend for her to have any part at all in the

story at the outset. To some extent

Violet is a character required by research. Every book I read about the Mary Celeste contained

a section about Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “The

Testament of J. Habakuk Jephson” in which the narrator purports to solve the

mystery of the ghost ship. This story,

which you can read here

http://www.readbookonline.net/readOnLine/2665/-

is a colonialist fantasy of the most

deplorable order and sets forth as fact some complete falsehoods, such as that there

were passengers on the ship and that some of the sailors were black men.

Doyle was a young writer trying to sell his

stories and he hit upon the famous mystery as a way to make his mark. This was before Sherlock Holmes entered and

overtook his brain and his life.

Dig just beneath the surface in

Doyle’s biography and you will discover that he was an avid Spiritualist who

spoke to his dead son every day (a son who had disliked his father’s mania for

seances), and gave over writing in his last years in favor of endless

proselytizing, lectures, and seances, bringing what he believed was the last

great religion to the skeptical and the unenlightened all over the world.

Before I commenced my pursuit of Conan Doyle, I had no idea

how wide the net the Spiritualist movement cast over 19th century actually was

and how tangled in it various literary

and political figures in American and Europe became. Wealthy families consulted mediums regularly

and as these were often young women with no fortune and nothing to offer but

their ability to communicate with dead people,

it wasn’t unusual for them to be invited to live with their

benefactors. Another pastime wealthy men

of science enjoyed was forming groups dedicated to exposing the mediums as

frauds. Conan Doyle at first posed as a

skeptic but he was ludicrously credulous and impressionable. It was rare for him to meet a clairvoyant he

didn’t entirely trust.

When I realized that I wanted Sarah’s younger sister, who

first appeared to me as a rebellious romantic, to actually become a famous

medium my heart sank. I have no patience

for that sort of thing. The whole

business is repellent and I assume most mediums were frauds who took advantage

of other people’s grief. Violet took me

a bit by surprise, with her sharp sense of humor and her apprehension of the

impossible situation she has gotten herself into by indulging in girlish

fantasies about herself. The older she gets, the more she perceives the exact

dimensions of the cage she has walked into. I originally didn’t intend ever to

go into her consciousness, nor did I realize she’d had a sad little affair in

her past until she got on the ship to England.

I always yawn when writers talk about how their characters

surprise them, but not because I don’t know what they’re talking about. Violet is loosely modeled on a student I once

had, a very pert, smart, sharp, dark little person who always listened to me

with an expression of mild skepticism and amusement. When I gave her good advice she would say,

with a tilt of her head, “that’s very interesting, Valerie.” To some extent the surprise comes from just

how much a character’s motives and decisions are ultimately predicated on what

might best be described as a manner.

range of viewpoints in this narrative seemed to me a deliberate choice, almost

as if the reader were a psychic surrounded by spirits, listening to their

voices! Did this play any part in your planning or was it more of a

subconscious choice?

The novel began with the usual struggle to find an angle, a moment in

time, a voice assured enough to draw the reader into the world of the

story. I made false starts: a first person

voice, a diary, a third person omniscient know-all-god-of-all-from-whom-nothing-is-or-can-be-hidden

voice, a straightforward, straight-talking third person acquainted with the

facts and recalling them from a safe and distant vantage voice, a close third

person voice that appears to be thinking aloud.

I had stacks of handwritten pages all over the table, each a different

section with a different voice. I’ve

never done that before, so I was extremely anxious. But there was nothing to do but keep

generating voices and see if they didn’t start to converge, which is what

happened. Chronology was another problem

I won’t go into.

For the last of the four years I worked on this novel, I

heard voices myself. I would wake in the

night and hear people talking. I

couldn’t make out a word they were saying.

I wasn’t even sure what language they were speaking. At first I thought it was a radio, the

neighbors, a hum in the walls. I got up

and walked around the house trying to find the source of the voices. After a while I gave up and went to

sleep. But often I woke, noted that I

could hear people talking, distantly, softly, monotonously. I ignored it and went back to sleep.

The day I finished the novel these

night-time voices stopped.

So the answer to your final question is definitely yes, the

mosaic of voices crossing and interrupting and distracting one another in this

novel was not something I planned. It

was clearly, as you suggest, a pressing

and irresistible subconscious choice.

A huge thanks to Valerie Martin for such interesting answers and for giving us a privileged insight into her writing process. Thanks also for the fascinating images, which were all provided by Valerie herself.

THE GHOST OF THE MARY CELESTE is out now in paperback from Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

You can find Valerie online here: