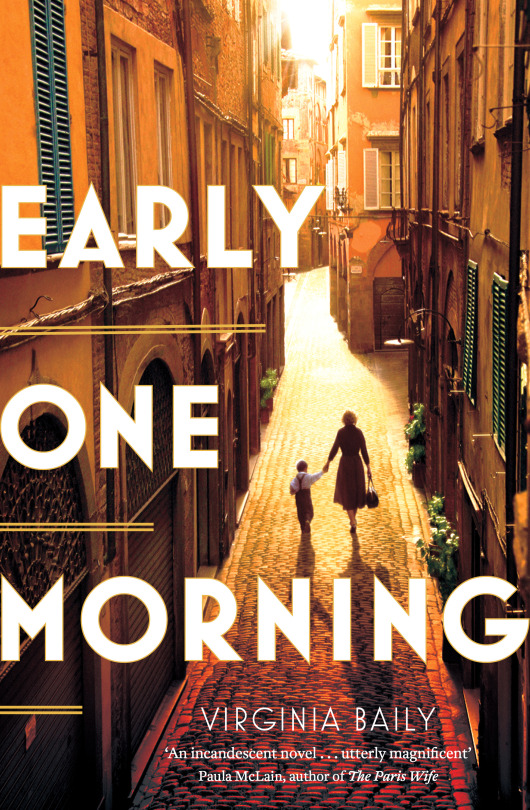

Good morning! I’ve been away from the blog for a while, so I’m delighted to be back with a super interview from Virginia Baily, author of the beautiful new novel EARLY ONE MORNING.

I discovered this book by chance, after seeing the cover on Twitter. Believe me, the narrative inside is as gorgeous as the cover. The story ranges from Rome to Wales, from wartime to recent history, a poignant and honest account of the personal cost of love and what makes a true family.

[1] There are so many different angles one could take whendealing with a subject like the Holocaust and this setting of Rome was an angle

that was certainly new to me. What prompted your interest in this part of

history?

Via dei Cappellari.

Were you once a young woman in Rome?

You write so convincingly from this viewpoint, I wondered if you were! Can you

also tell us about some of your research methods for the settings of this

novel, in time and place?

My aunt, who is

also my godmother, lives in Rome and I first went to visit her there at the age

of 16. I have been going back ever since. The story of the genesis of the novel

is the story of my love affair with Rome. Many of the elements of my first

visit find a place in the book – the fabulous food, the colours, the heat and

sunshine, the effect of the beauty, of being surrounded by it and feeling its

glow, the sound of Italian, the urgent need to speak it, the discovery of a new

version of me as a ‘bella bionda’ and foreign and unexpectedly exotic. Maria,

the young girl in EOM, is not me but much of her experience of Rome echoes

mine.

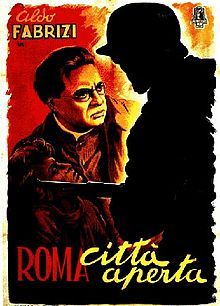

My fascination

with war-time Rome was first sparked by the novels and films I studied when

doing a degree in Italian. Rossellini’s

film ‘Rome Open City’ set and partly filmed during the German occupation

probably came first and was an eye-opener.

Later on I did some research into resistance literature and I came

across an account of the round-up of the Jews of Rome on October 16 1943

written by a Jewish writer called Giacomo Debenedetti. The impact of that on me was huge and

amplified by the fact that it all took place around the corner from my aunt’s

apartment in the street where we went for our morning coffee.

So, to some

extent, the research for this novel has been an ongoing process over the course

of my life! But I had to refresh my knowledge and add detail and for this I

read and re-read novels written in the periods where mine is set, watched films

for the first or umpteenth time, read first-hand accounts / history books,

examined hundreds of photographs of Rome then and now…

I also went and

lived for a more extended period in Rome while I was actually writing the book.

I won the McKitterick prize for my first novel, ‘Africa Junction’ and used the

prize money to rent a flat in the San Giovanni area. In the mornings I wrote

and in the afternoons I roamed Rome!

The real-life setting where the character Chiara lives in Early One Morning.

[2] You use different tenses for thedifferent time periods, interestingly, using the present for the oldest section

and past for the newest. How did this decision come about and what effect do

you feel it has on the reader?

My default

setting for telling a story is third person past tense and there has to be good

reason to stray…

The present

tense gives a feeling of immediacy, of events unfolding in that precise moment

and, because the war-time stories are history in the making, it seemed the best

way of articulating that. For my heroine, Chiara, life is tumultuous and

ever-changing. She is at the mercy of

massive, historical seismic movements, of people, of bombs, of armies and she

is just a pawn; only able to react, make split second decisions without knowing

what their consequences might be. The present tense has a drama and a

life-on-the-edge-of-a-blade feel to it.

The tense

choice is also (I intended and hope) a way of quite subtly signalling to the

reader which time period she / he is now in without overtly flagging it up.

There was something perversely pleasing about the contrariness of it – that the

older story is told in the present tense and the more recent one in the past

tense. But it also mirrors Chiara’s

stage of life – the present tense when she is young and unformed and the past

tense later when she is more reflective, what’s done is done and she has to

live with the consequences.

Portico di Ottavia area where Gennaro’s bar is found in the novel.

[3] The character of Daniele is acomplicated one and we never jump inside his head, seeing him only from the

outside. Anyone without a heart of stone would hugely sympathise with his

circumstances and yet there are aspects of his personality that perhaps could

be seen as somewhat unsympathetic. Was this a conscious choice on your part or

did he just develop that way of his own accord? (Personally, I find that’s what

makes him so interesting! Of course, perfect characters are a deadly bore!)

Daniele is partly characterised by his absence and his

unknowability and so the decision not to jump inside his head was a deliberate

one.

I did think hard at the outset about what the impact

of something of that magnitude on a small person’s psyche might be. I looked into the effects of deracination,

survivor’s guilt (aka post-traumatic stress syndrome), the motives for and

manifestation of self-harm, reactive mutism.

But, when it came down to it, his complex and challenging character

evolved with the forward movement of the narrative. Something seismic and disruptive and

extraordinarily painful was set in motion inside him when his mother pushed him

away and singled him out for a chance at survival. I didn’t set out to make him

tricky. He just was. How could he have

been anything else in the circumstances?

A street in the Rome ghetto.

[4] There was one key phrase thatreally struck me: “That he doesn’t want to be saved. He never really

did.” This story of full of moral complexity. Nobody is ideal and everyone

has made mistakes. Chiara herself makes decisions of which she is deeply

ashamed. How did this moral complexity develop for you in your planning of the

narrative? Did it simply come naturally with the territory or was it something

you consciously wanted to explore?

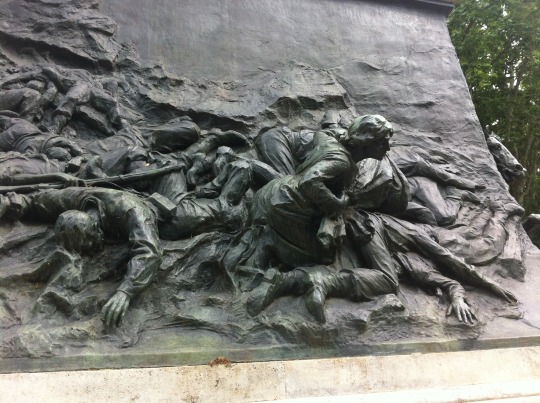

Debenedetti’s account of the round-up of the Jews is

an amalgam of many eye-witness reports. One of the anecdotes he relates is of a woman who attempted to claim one

of the children being deported as her own.

But the child screamed for its real mother and was handed back and thus

lost. And ever since I first read that, I have wondered: How might it be if the

child did not scream, or did not scream loudly enough to be noted, or if the

forcefulness and conviction of the woman who had claimed the child somehow

overrode the screams? If she succeeded

in making him be quiet. How might that be?

The deportation plaque commemorating the event.

Decades later, when I embarked on this novel, I was still

haunted by that question and that child but it seemed to me too difficult a

story to write. I originally set out to

write a different novel, a coming-of-age story set in Rome in the 1970s. But

that child still haunted me. I tried to

pull the blinds down and shut him out, but he dumbly, insistently kept knocking

at my window. So

I wrote the first chapter almost to get him out of the way. I wrote it like a short story, as a

stand-alone piece so that Chiara’s action in saving him would constitute an

ending. Obviously an open ending, with

lots of unanswered questions, but still, an ending.

Then I tried to concentrate on my bildungsroman.

But the child, given a solid

presence now, was in my head. I hadn’t

succeeded in silencing him at all. I had done the opposite. I had brought this

uprooted, traumatized child to life and now I had to do something with him. It

wasn’t an ending. It was a beginning.

So I didn’t set out consciously to

explore the moral complexity but, having set up the premise, in the end there

was no way of avoiding it. Daunting though it was, I had to go there. Yes, it

came with the territory.

Occupied Rome.

[5] I noticed there are some sceneswhere key moments are seen from the point of view of a peripheral character,

such as Assunta, the cleaning lady. Why did you decide to use such a viewpoint

and how did you feel it served the narrative?

Assunta was a character who arrived

fully formed, with her opinions and her attitude and her different

perspective. To see the narrative unfold

through her eyes at certain key junctures allows a different facet of the story

and the characters within it to be presented. She contributes to our

understanding of what makes the central characters tick. Assunta is there right in the middle of it

all but she is not a protagonist and so it is almost as if she is able to lift

a curtain for the reader and invite him / her to look behind. Although I didn’t think of it at the time, I

did wonder at myself afterwards for having chosen to offer the viewpoint of

such archetypal bystanders / moral arbiters as the serving woman and the

priest. Some faint, unconscious and unrecognized-at-the-time Shakespearian

influence going on there perhaps!

Garibaldi monument detail.

[6] Please tell us about your workwith Riptide and the Africa Research Bulletin. Also, would you be able to share

anything of what you’re working on next?

The Africa Research Bulletin is a twice-monthly digest

of economic and political news dealing with the whole African continent. It’s

primarily a research tool. I work on

both bulletins and am the editor of the political one.

Riptide is a short story journal/ anthology I set up

about seven years ago with my friend and fellow writer, Sally Flint. We thought there weren’t enough outlets for

short stories in the UK and decided to do something about it. So far we have published ten books and we

have just made a call for submissions for our next volume – the theme is Carpe Diem and the deadline is November.

I have started work on another novel but it’s early

days. I can tell you though that a character from ‘Early One Morning’ has stepped

across into the world of the new story. Solid objects are often a way in for

me. I seek the connections between disparate objects and the tale might hang

from these connecting threads. In ‘Early One Morning’, a list of such objects

would include a sewing machine, a signet ring and a trumpet. The new novel

features a set of kitchen scales, a pair of ballet shoes and a blindfold.

Thanks to Ginny for such detailed and fascinating answers. You can find links to her books and other projects online here:

https://twitter.com/GinnyBaily?lang=en-gb

https://twitter.com/RiptideJournal?lang=en-gb

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Virginia-Baily/e/B00698T8SC/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0

https://hachettebookgroup.com/titles/virginia-baily/early-one-morning/9780316300391/

http://www.riptidejournal.co.uk/

https://africaresearchonline.wordpress.com/about-africa-research-online/