It’s a pleasure to welcome back to my blog Martine Bailey, whose second novel THE PENNY HEART has just been published a few days ago (Hodder & Stoughton).

It’s the tale of two women, romance, and revenge. The Sunday Times gave it a smashing review:

I enjoyed the book immensely – a rollercoaster of a plot that was full of incident and drama, with compelling, richly-drawn characters. Here’s what Martine had to say to my questions:

[1] Tell us about the real practice of penny

hearts.

In 1788 the British government sent the first

criminals from its overcrowded prisons to Botany Bay, Australia, a green shore

named by Captain Cook for its variety of botanical specimens. To some convicts

it was seen as worse than hanging, as the Antipodes, at least eight month’s

voyage from Britain, were viewed as ‘the ends of the earth’. Penny hearts, or love tokens, were smoothed copper

pennies engraved by convicts with messages to loved ones to remember them by. The

convicts were desperate people about to embark on the Georgian equivalent of a

trip to the moon with almost no prospect of return. Though believed at the time

to lack all humane feelings, they left messages of desolation, pain, defiance

and anger. I mention one poignant coin in The

Penny Heart: a woman who depicted her dog in her cottage garden and the

words: ‘This was once my cottage

of peace…Going out of her cottage for life, E.A.’ A male

convict depicted in irons wrote: ‘How

hard is my fate, how galling is my chain.’

As well as words there is a rich selection of imagery,

such as ‘Mary Eater’ and her barrow

of fruit or vegetables and another woman releasing a dove beside an anchor of

‘Hope’ and the words ‘I

Love till death, shall stop my breath’. We know from surgeon’s

reports that these tokens share the same rich iconography as tattoos: the

chains, anchors, Irish harps and mythical figures that convicts also inscribed

on their skin as statements of defiance.

[2] In this book, there is a harsh and honest edge

to the writing, which is very much anti-costume drama! Can you explain this

writing style to us – is it deliberate or just the way it comes out?

I would say that it is the subject matter that is

harsh, and the writing had to reflect that. Because I wrote the opening when I

was living in New Zealand I chose the collision of two subjects – what was happening

in the 18th century in that part of the world, and my own identity as a British

Northerner. The 1790s were a fascinating time, when the Australian penal colony

was struggling to survive, while at home the French Revolution was casting a

dark shadow over a class struggle in the industrialising North.

Once I had read the actual words of convicts, in

letters, trial reports and slang dictionaries of the day, it didn’t seem

appropriate to use the standard 18th century language of ‘civility’.

Particularly when I was writing Mary’s

chapters, I had the criminal slang of ‘cant’ in mind, and though aware that too

many obscure terms would make it incomprehensible, I wanted to give a flavour

of that vibrant culture.

As for being anti-costume drama, I would say that BBC

2’s Banished interpreted a few of the

same events with a lot more testosterone! By contrast, I wanted to present the

women convicts’ experience, so the Great Storm needed to be shown. On their

first night on land a nightmarish sexual free-for-all was allowed by the

authorities, because it was ‘only to be expected’ after months of male

incarceration. I’m glad you picked up on

the honesty, as I wanted to forcefully contrast Mary and Grace’s experiences,

as a result of the ‘lottery of life’.

Plas Teg.

[3] Is Delafosse Hall based on a real place? Tell

us about the English settings in your book. Did you, for example, wander the

streets of York?

Delafosse Hall is a hybrid of a number of historical

locations. I imagined the facade to be Plas Teg, a Jacobean manor near my home

that once featured on the BBC’s ‘Country House Rescue’. For many years it was

abandoned until it was refurbished by Cordelia Bailey (no relation) and it

still has areas of complete dereliction. The carved Jacobean staircase is similar

too, as is the underground kitchen.

But to be honest there are bits of other houses,

too – the Hunting lodge is not dissimilar to The Cage at Lyme Park, and the

general sense of ruin was inspired by Calke Abbey.

Yes, I did walk the streets of York. One particular

scene was set in the Assembly Rooms (now an Ask

Italian restaurant) that still contain the original Corinthian pillars.

I know

York quite well, through repeated visits to the wonderful Fairfax House, a

centre for many Georgian events and publications.

(*interrupts* I visited Fairfax House too, when I was researching SONG OF THE SEA MAID. It’s a wonderful treasure trove of C18th bits and bobs, isn’t it! I used the kitchen there as the basis for the one in Mr Woods’s house.)

It was a pleasure to write

those scenes, because like Grace, it was good to have a break from Delafosse

Hall in a bustling, beautiful city.

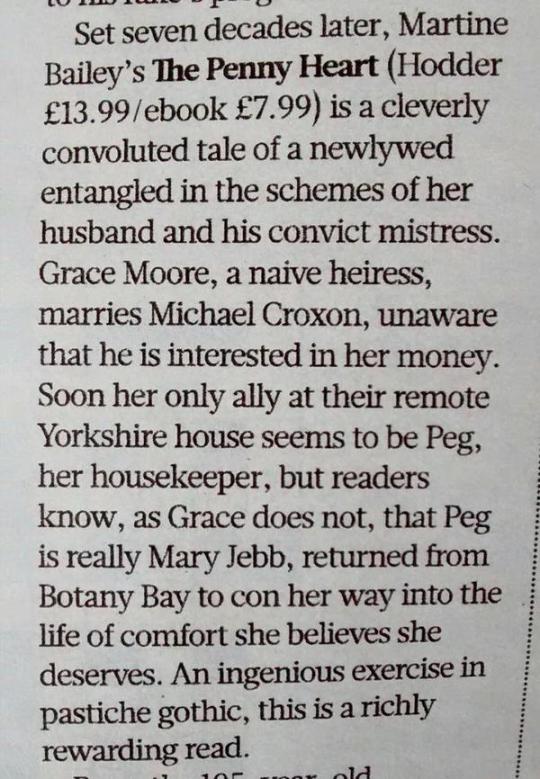

The scenes in London had more literary and online

inspirations. Golden Square was well described by Thomas de Quincy as an area

of genteel poverty and there are lots of accounts of Newgate and St James’s

Park. Like Sydney, some parts of London are so layered with subsequent development

that it can be easier to describe them from old prints than find evidence of

the past today.

[4] What recipes did you try out whilst writing

this book? And which is your favourite?

So far I’ve only tried the more familiar

recipes: Apple Pie, Pease Pudding, Cherry Trifle, Gingerbread, Yorkshire Fat

Rascals and some of the decorative sugarwork. The gingerbread is a particular

favourite of mine, though the recipe I give is bulked out with additives to maximize

profits. Wooden

moulds for gingerbread have a long tradition, carved in the shapes of carriages

and animals, heroes and monarchs. There were romantic associations too, in the

baking of gingerbread ‘husbands’ and ‘wives’, bought by sweethearts as ‘fairings’.

The gilding of gingerbread gave it a glittering appeal, recollected in the

proverb Grace reflects on as she becomes disillusioned by her husband: To

take the gilt off the gingerbread. (Meaning: the fading of an item’s glamour.)

Gingerbread

The

Georgian era was an age of ‘remedies’ and elixirs, peddled by criminal quacks

and charlatans. I spent a long time looking for quack recipes until it

dawned on me that of course these were entirely secret. There are hints,

however, in home remedies such as Poppy Drops, to help the imbiber sleep, or

old wives’ cordials made from narcotic herbs to help women in labour fall into

a ‘Twilight Sleep’. In the United States the

novel will be titled A Taste for

Nightshade, reflecting Mary’s fascination with sinister additives.

I did try some extraordinary food on my travels,

including Maori foods cooked underground with hot stones in a Hangi pit oven. I also ate kangaroo,

crocodile, paua (black sea snails), campfire damper and grubs. I wanted to look at recipes

from a different perspective – as quackery and aphrodisiacs and also at an

absence of food on people and the extraordinary trust we show when we eat food

made by a stranger’s hand.

Hangi pit oven

On a

lighter note, when I came back to the UK I embarked on

learning period sugarwork with food historian Ivan Day and was fascinated by

tiny sugar devices, such as a doll-sized bed to be placed on a bride-cake and a tiny cradle and swaddled baby. Just as we might treasure the

‘cake-topper’ from a wedding or Christmas cake, these are symbols of hope and

fecundity. In the novel however, they do have a double-edge; though beautiful

objects, they are in the end fragile, lifeless, and of course ultimately

edible.

[5] The Australia and New Zealand sections were

particularly compelling for me. I see from the Acknowledgements that part of

the book was written there. Where did you stay and where did you wander? How

did this inform the book?

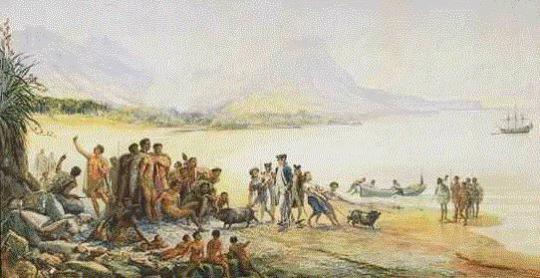

My son Chris lives

out in New Zealand, so it had been an ambition of ours to spend some time with

him and possibly emigrate. Then in February 2011, Chris and his partner were

caught up in the Christchurch earthquake and we speeded up our application to

go as sponsored parents. In September 2011, my husband Martin and I flew out

there after arranging a series of house-swaps through home exchange websites. For

our first year, we lived on New Zealand’s East Cape, with an ocean view of the

Pacific studded with the same volcanic islands as those recorded in Captain

Cook’s Journal. The solitude and sense

of distance and disjunction from Britain was an immense influence on The Penny Heart.

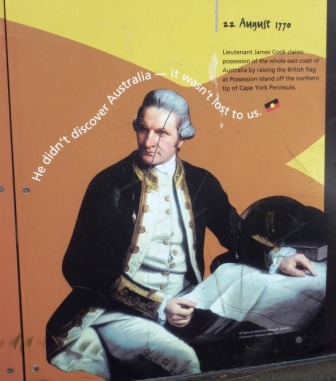

Cook in New Zealand

Martin was

teaching Maori youngsters and photographing local people for a Creative Arts

exhibition, so I was fortunate to get a glimpse of the strong local traditions

of singing, tattooing and celebration around the Maori meeting grounds or Marae.

After our first year, we

travelled more, spending time across the Tasman Sea in Australia. There is

political ambivalence about the First Fleet now, and I found it poignant to

visit the plants in the Botanic Gardens, the last remnants of the first Government

Farm. My highlight was a boat ride to Parramatta, where the Governor’s house

and first settlers’ farms are cherished by heritage institutions.

By this time, I

was dealing with my editor at Hodder nearly every day by email and it became

clear that we would return home to the UK. We spent our last months in Auckland

where we lived and worked in an eco-house, and I also gained

a place on the New Zealand Society of Authors’ mentorship programme. In New

Zealand we both gained from the uncomplicated ‘can do’ attitude – which I still

miss, along with the comfortable modern libraries with the best views in the

world.

[6] Your writing is rich with historical detail.

Take us through your writing process in terms of how precisely you organise

your 18th-century research into the fictional elements.

The Penny Heart began with memorial objects such as the Penny

heart itself and the factual history surrounding it. Next, I read a great deal,

photocopy interesting history, make lots of notes in notebooks and start to

sketch out the conflicts between characters. My favourite bit is to decide

where and how I can go on research trips – the chance to get out and learn

something new is always attractive.

My day-to-day process is to use a series of thick

notebooks that I scribble nearly everything in as I am writing. This has

brainstorming, mind maps and scraps of dialogue, a timeline and even sketches

of costumes and rooms. I also have a shelf of labelled magazine boxes where I

keep information on subjects such as food, locations, museum brochures, and so

on. Later, I usually set up a big corkboard with images. At some point in every

novel I find myself tested by the sheer amount of research and sadly about half

of it doesn’t even get into the final book.

[7] The two female protagonists – Grace and

Mary/Peg – are opposites in many ways. How did you come up with that idea, to

tell the tale of two contrasting women in juxtaposition?

Again, I think the situation I was writing in

suggested contrasts on many levels, whether between wild convicts and respectable

pioneers, or between myself as a new migrant and my more comfortable life in

Chester. Then of course, we were

literally ‘house-keeping’, inhabiting other people’s homes, driving their cars

and using their household goods – an interloper’s role experienced by both

Grace and Mary. Moving to a new country brings an untethering to the past while

simultaneously seeing your past self and your home nation in sharper focus.

That, I suspect, is why so many writers place themselves in various kinds of voluntary

exile. We also met many migrants who had that kind of split in their identities,

and one of my richest experiences was listening to migrants from China and

other parts of the world and thinking about their struggles to bridge the gap

between their old and new selves.

Of course there were lots of literary influences,

too. I remember studying Paradise Lost

and how even Milton struggled to make God an engaging character beside the

fallen glamour of Lucifer. Mary arrived

fully formed as a character; I immediately admired her cleverness, her pluck

and courage. Grace couldn’t help but become the observer of events, a sensitive

everywoman who is forced out of her passivity. I did have a long struggle over

who should prevail!

I like using a dual narrative because it heightens suspense,

as neither character knows the entire story – but the reader can actively try to piece it

together. I didn’t find it easy, and there had to be many re-drafts because of

the time jumps in Mary’s backstory. I also love this form in the contemporary

crime novel, for example Barbara Vine/Ruth Rendell’s psychological novels,

where much of the fascination with criminal behaviour arises from the reader

observing both victim and prey.

[8] What’s up next for you and your writing?

At the moment, I am pleased to be living in one

place again, back in Chester. The Penny

Heart has just come out so there are lots of talks and events to prepare

for. I do have a synopsis and opening for Book 3 and am thrilled my agent likes

it. All I can say at the moment is that it is set in the countryside and I love

the new idea and the Georgian documents that inspire it.

Thanks so much to Martine for fascinating answers – such detail and thought shows clearly that here is a hard-working novelist with impeccable research. If you like the sound of THE PENNY HEART, you should also check out Martine’s first novel, AN APPETITE FOR VIOLETS. I interviewed Martine about that here:

http://rebeccamascull.tumblr.com/post/108249339433/interview-with-martine-bailey

and you can find Martine online here:

https://twitter.com/MartineBailey?lang=en-gb

https://www.facebook.com/MartineBaileyWriter

https://www.pinterest.com/biddyleigh/an-appetite-for-violets/