I recently reread this classic book and was in awe! I knew it was brilliant, but reading it as an older, somewhat wiser reader I was quite amazed at the virtuosity of Dickens’s writing here. Itching to discuss it with someone equally enraptured, I put the call out on Twitter and found Katherine Muskett @Compleat_Reader and Helen Stanton @Helannsta to share the joy. We had an email conversation about the great book. Here’s what we had to say:

Katherine:

First of all I should say

that I am not huge fan of Dickens. I haven’t read all of his books (apart from

GE, I’ve read Dombey & Son, A Tale of Two Cities, A Christmas Carol and

Oliver Twist). What I love about GE is that Dickens keeps the plot relatively

streamlined. Although he deploys many different genres & literary

techniques, they all seem subordinated into the book’s psychological realism.

In the first part of the novel, I think he manages to successfully intertwine

the child’s perspective and adult understanding (which is no easy task). As Pip

is growing up the reader can see the mistakes he is making (his treatment of

Joe, for example), but by interlacing it with the remorse of the adult narrator,

it allows us not to lose sympathy with him. The other feature I love about

this book is that (unlike some of his other novels) is that he never descends

into sentimentality.

The book has for me tremendous energy and I think that is in part to do

with its serial publication – the need to keep the reader coming back for the

next instalment.

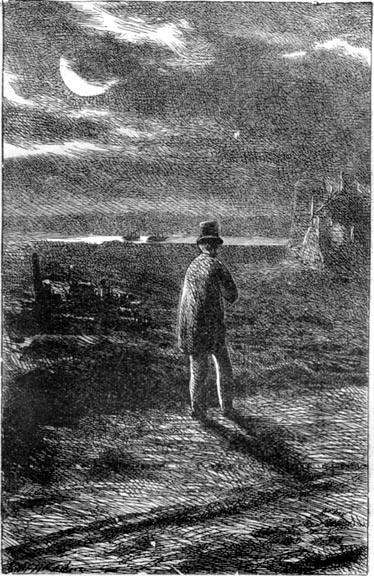

Pip all alone, near the Lime Kiln.

Rebecca:

I

suppose I should lay my cards on the table and say I AM a huge Dickens fan! But

with the proviso that I don’t love all his books equally. There are a couple

that I won’t lose any sleep over never reading again, that’s for sure. But he

was so prolific, I guess he’s allowed a few duds. And I agree that as Dickens

goes, he nails it in Great Expectations. I think you’re absolutely right about

the matter of perspective. It would be very easy to judge Pip harshly,

particularly the young man Pip who betrays his roots and – let’s face it –

becomes rather an insufferable little snob. Yet the older, wiser adult

perspective looking back so cleverly allows him to comment upon himself and his

failings, that one cannot fail but feel sympathy – there’s a great bit where

he’s come back from London to his home town and is persuading himself that it

wouldn’t be right to stay back at the old forge with Joe and instead lodges at

the Blue Boar and the older voice says: “All other swindlers upon earth

are nothing to the self-swindlers, and with such pretences did I cheat

myself.” There are just dozens of these little gems in the book, that

wisdom, that knowing look at our failings.

And

this contributes to what you so rightly said about psychological realism. Those

insights into human nature are present in every character, from the major ones

like the jilted Miss Havisham to marvellous little walk-on parts like Trabb’s

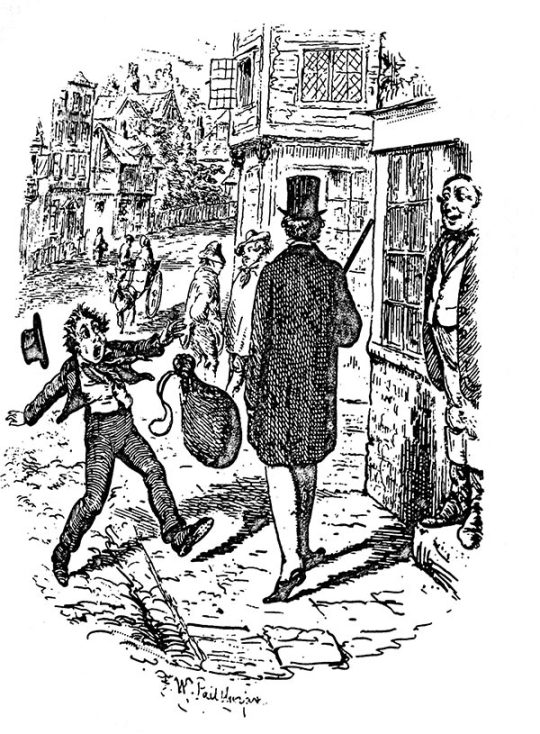

boy, who taunts the newly-minted gent Pip as he struts down the street,

shouting “Don’t know yah…pon my soul, don’t know yah!“ That kid certainly

has the measure of Pip! I just love Trabb’s boy and all those Dickens folk who

leap off the page.

Trabb’s boy mercilessly mocking Pip!

And here I come to a criticism often hurled at Dickens, that

he only writes caricatures. I get that, I can see what people mean – but I just

don’t buy it. Dickens achieves this rare, rare thing, as he writes such

entertaining stories full of fascinating characters, but at the same time he

has such a deep and precise understanding of the human condition, that all our

foibles and weaknesses and our loyalties and moments of greatness are shared

out equally amongst all characters – such as Joe Gargery, at one moment we are

laughing gently at his ridiculous posturing when he visits Pip in London and

tries to fit with his idea of gentlemanly conversation: "I meantersay…as

it is there drawd too architectooralooral.” But moments later, we see his

innate dignity when he says to Pip: “You won’t find half so much fault in

me if you think of me in my forge dress, with my hammer in my hand”.

Pip and the wonderful Joe Gargery.

I’m

really interested in what you said about sentimentality too – can you expand on

that for me? Where is it you feel Dickens avoids this in Great Expectations?

And

also can you tell me what genres and techniques you appreciate in the book?

Katherine:

I

think that Dickens (in GE at least) is an expert manipulator of genre,

combining forms and generic conventions in all sorts of entertaining &

illuminating ways. In particular, the deployment of the gothic in his creation

of Miss Havisham. Although she appears weird and fantastical to the young Pip,

her strangeness beautifully communicates her breakdown in a way that seems to

me entirely authentic and believable. Trabb’s boy is another example of

Dickens’ generic flexibility. I know what you mean about caricatures, but

surely the whole point of a caricature is that we recognise ourselves in it?

We’re all capable of self-delusion, snobbery and weakness (and perhaps that’s

another reason that we manage to keep faith with Pip?).

Pip, the skeletal Miss Havisham & the great bride-cake, crawling with spiders.

As

well as aspects of the gothic, I think the story draws on other traditions and

conventions. There’s a sense of moral fable, as eventually Pip comes to

recognise that Joe is the true gentleman. Pip sees himself as a sort of fairy

tale character too (at least until his fall from grace), and Estella as his

princess. Underneath that there’s a deeper tale of moral redemption – not so

much of Pip, but Magwitch. Dickens’ treatment of the convict is compassionate

& Magwitch’s court appearance is a fantastic piece of social commentary.

Compared

to Dombey & Son (the Dickens novel I know best after GE), the deaths are

largely free of sentimentality. Of course there are no children or mothers

dying within the narrative, which helps! Pip’s two flawed mothers (Mrs Joe

& Miss H) die but as neither of them have been Dickens’ ‘Legless Angels’,

there is less emotional weight attached to their deaths. Magwitch’s death

is moving but I think it’s lifted above pathos by his earlier performance in

court.

Restoration House, Rochester, the model for Satis House, Miss Havisham’s haunted, crumbling mansion.

Rebecca:

Your

email was so fascinating, I read it several times and then it sent me off to

read George Orwell’s essay on Dickens!

Orwell

criticises the messages present in Dickens’s works, as illuminating social ills

and yet suggesting no remedy. I love Orwell in many ways, but I’m not sure I

agree that it should always be the novelist’s job to provide answers. The very

fact that a middle-class man like Dickens was highlighting the plight of

convicts sentenced to death – in that wonderful court scene you mention where

the faces of the condemned are described in wonderful and pathetic detail – and

through a character like Magwitch, allows the reader some insight into how such

a man is formed. The chapter where Magwitch describes his desperate upbringing

is so poignant and Pip’s change from horror and revulsion at the sight of

Magwitch to wishing to spend every moment with him before his death is an

extraordinary transformation, and one in which Dickens shows us the possibility

of seeing people in all their complexity and avoiding simplistic labels, such

as ‘convict’ or ‘gentleman’. As you say, Joe is a true gentleman, and Magwitch

a loving father by the end of the narrative, something which seemed impossible

at the beginning.

Pip meets a haunted-looking Magwitch in the graveyard.

Although

Orwell criticises many aspects of Dickens, he does have tremendous respect for

him too, and at one point makes this claim:

no novelist has shown the same power of entering

into the child’s point of view.

Great Expectations begins with the child, in a similar way to David

Copperfield, yet GE goes deeper into the complex moral sense of how it feels to

be inside the child’s mind. Right from the beginning, Pip is laden with guilt

about almost everything he does. Being caught by a convict haunts the rest of his

life, of course, but not only in the narrative sense (as the convict becomes

his secret benefactor) yet also in a sense of guilt.

Child graves at Cooling Church, said to be the inspiration for those of Pip’s family by which he stands shivering at the book’s opening.

Pip commits a crime in

helping the convict – theft of food and the file – for which he is never

punished. On his way with the stolen goods he imagines objects animate and

inanimate accusing him – ‘Young thief!’ And he never really gets over this

fear. As a young gentleman, when Estella comes to visit in London, she sees

Newgate prison and asks him about it, to which he pretends he knows nothing

about it and yet we know he has recently visited there with Wemmick. He has

been brought up in a particularly strict, moralistic and critical atmosphere by

Mrs Joe and Uncle Pumblechook, who accuse him of being capable of all manner of

terrible things, on no evidence.

Yet,

perhaps we are all raised in some aspects of this – all children are told off

for behaviour that does not seem wrong to them, so that they are constantly

learning which are the correct desires and those that require denying. That

sense of guilt and wrongdoing that Pip carries around him – I believe this goes

towards the deep psychological realism you mention, but despite the mythical

quality of some of the settings and characters, there is always this sense that

the reader knows Pip deeply, indeed in our own childhoods we ARE Pip! It’s this

ability to look back and forgive children their failings and mistakes on the

road of experience, that allows us to keep faith with Pip but also to forgive

ourselves a little bit too.

The ‘coarse, common’ boy Pip and proud Estella.

The

fairytale aspects you mention are very interesting – you’re absolutely right

that Pip sees himself as a kind of prince, rescuing Estella from the wicked

witch. And Satis House is like a kind of bewitched castle, such as that you

might find in Sleeping Beauty, whilst the truth about Estella is in fact that

she has a heart of ice, like the Snow Queen. And all this serves to present the

reader with powerful, memorable imagery – such as the astonishing scene of the

bride cake infested with spiders. Yet beyond this, Pip learns that life is not

a fairytale, and in Dickens’s original ending, things do not end happily ever

after. It is a very honest novel in that way, that Pip has his illusions

shattered and thereafter – instead of coming home with the great prize – he

simply makes the best of things, as we do in our real lives. I have a real soft

spot for the hero’s journey as a narrative, yet the realist in me also sees its

fakery. The brilliance of Great Expectations is that it merges the fairytale

and the real, in a way perhaps no other Dickens novel does so well.

Katherine:

I’ve been flicking through GE & noticed the way in which Dickens turns

people into objects & animates objects. Wemmick is described as having a

‘post-office of a mouth’ (vol 2 ch.2] and Miss H becomes increasingly

identified with her rotting cake; Drummle is ‘a heavy order of architecture’

(vol 2 ch. 4). Objects become animated (usually malevolently) in ways

that externalise Pip’s sense of guilt – ‘a meek little muffin confined

with the utmost precaution under a strong iron cover’ (vol 2 ch.14), not

long after he ‘had Newgate in [his] breath’ (vol 2 ch. 13). Jaggers ‘stood

frowning at his boots as if he suspected them of designs against him’ (vol 2

ch.17). As Pip’s fairy tale collapses he lies in bed ‘the closet

whispered, the fireplace sighed, the little washing-stand ticked’ (vol 3 ch.6).

I think Dickens creates a sense of an almost malevolent world in which objects

are animated and people dehumanised.

Pip

is haunted by guilt throughout, which he traces back to the first encounter

with Magwitch but I can’t help thinking there’s an underlying sense of his own

wickedness, inculcated from birth. I wouldn’t quite call it Original Sin,

because his tormentors and accusers (Mrs Joe, Pumblechook) don’t seem to have

any sense of their own moral failures, but Pip is made to feel that he is

inherently wicked (it reminds me a little of Mr Brocklehurst in Jane Eyre and a

vicious desire to break the child’s spirit). In a sense perhaps, although I

don’t think it’s articulated anywhere, Magwitch is a manifestation of Pip’s

sense of guilt, even before he has stolen for him. One of the critics has

something interesting to say about a similar role for Orlick.

Uncle Pumblechook and Mrs Joe picking on Pip, as usual.

Returning

to Pip, I think at one point we feel Dickens talking to the reader directly

through him, in an extraordinarily moving passage (vol 1 ch.8) in which the

adult Pip describes his feelings of childhood injustice: ‘In the little world

in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, there is

nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injustice’ – the more times

I read that passage, the more I feel this is Dickens himself addressing the

world directly.

Rebecca:

I think you’re absolutely spot on as regards Pip being born with a

sense of guilt – he does seem to carry it about with him & it’s a brilliant

point that Magwitch is like the spirit of his shame somehow. Perhaps it stems

from the death of his parents and most of his siblings, and that Mrs Joe

constantly makes him feel guilty for ruining her life. Perhaps that’s partly

where the guilt comes from, a kind of survivor’s guilt in the first instance,

and then the guilt of being a burden thrust upon him in the same way Mrs Joe

detests her apron!

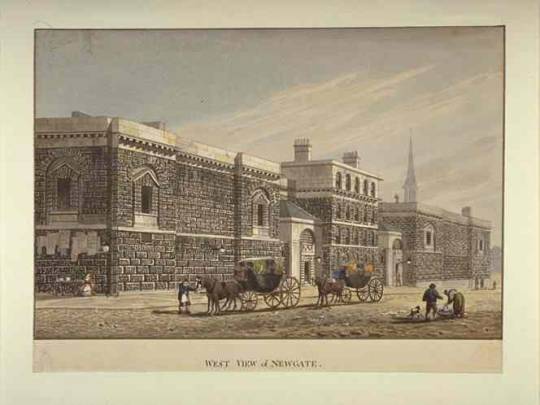

Newgate Prison in Dickens’s time, perhaps another manifestation of Pip’s guilt.

Helen:

My

Dad’s response to me when I was a young and (as I saw it) rebellious young

student and I told him (a huge Dickens fan) that I thought CD was unrealistic

with cardboard cut-out characters. My Dad just responded very calmly that as I

got older I would realise that CD captured the essence of human nature in a way

that very few writers since have been able to…and I have found that to be

absolutely true.

In

Pip he doesn’t just portray the bewilderment of an abandoned child but also the

sexual obsession of a young man totally unable to express himself because of his

life experience as well as social conventions of the time.

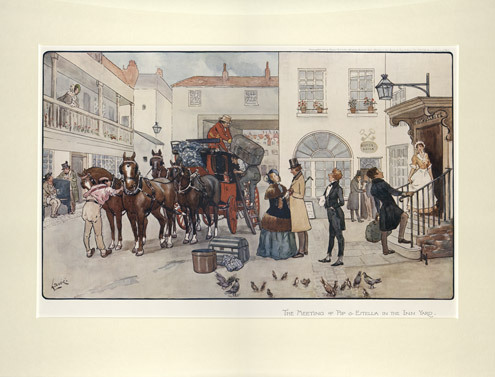

Pip meets Estella outside the Blue Boar.

I

think the only other point I would make is to agree with Katherine ….yes CD

did often create caricatures but usually he used them to highlight a serious

point about human behaviour. Miss H is a fantastic creation but she does show

how obsession and jealousy not only poison your own life but those of people

around you.

Finally, of course, there is his humour. He remains one of the few writers who can

make me laugh out loud on a train… What larks, Pip, what larks!!!

Rebecca:

Absolutely! Here’s a classic quote, pure Dickens comedy. Here is the description of a very minor character, Mr Hubble, yet one whose bandy legs will live on forever in my memory and, indeed, make me laugh out loud on trains:

“a tough, high-shouldered stooping old man, of a sawdusty fragrance, with his legs extraordinarily wide apart so that in my short days I always saw some miles of open country between them when I met him coming up the lane.”

In my short days!!

Sawdusty fragrance!!!

As my mum says, ‘Who could ever have thought of that except Dickens?!’