I loved Katherine Clements’s first novel THE CRIMSON RIBBON – a super mixture of romance, friendship, intrigue, historical accuracy and mystery – and I interviewed her about it here:

http://rebeccamascull.tumblr.com/post/97208287298/interview-with-katherine-clements

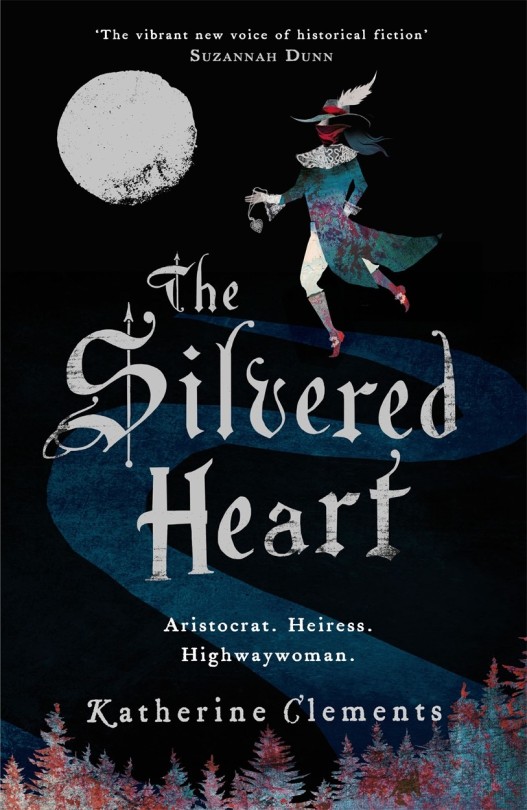

Now she’s gone and done it again with the marvellously entertaining yet hard-hitting THE SILVERED HEART, about a highwaywoman in C17th England.

So, I’m delighted to say Good Morrow, Mistress Clements (I’ve probably got that totally wrong, historically speaking) and welcome back to the blog.

[1] You include so many lovely historical details in your writing, such as

this: “Beams are garlanded with apple blossom from the orchards, white

petals wilting in torch heat, falling in pretty flurries of springtime

snow.” What kind of methods do you use for historical research and how do

you organise and then incorporate them into the narrative?

Research

tends to be a mixture of reading (fiction and non-fiction), watching (drama and

documentary) and visiting (historically relevant sites and locations). I start

by reading widely and then focus in on things that are relevant to the story

I’m working on. I love social history and the small details of everyday life.

I’ll make a note of interesting things as I come across them, like making a

deposit into an account full of images and ideas, and then draw on this when

writing.

When

I write, the scene is always very visual to me, so often I’m just describing

what I see – there is no master plan. Sometimes I do go looking for the right

image or detail to convey a sense of place or an emotion. I think it’s

important not to overdo it, no matter how much I might want to shoehorn in all

the fascinating facts I find. I try to include only details that are relevant,

or that my characters would notice.

and in this book you choose largely the opposite viewpoint, that of the

Royalists. What was your thinking behind this and how do the different

perspectives appeal to you?

The

main character in The Silvered Heart,

Lady Katherine Ferrers, was a real person who came from a Royalist family, so I

knew when I chose her as a subject that I would be writing from her point of

view. It was a challenge, having spent so long working with the Parliamentarian

and radical ideas in The Crimson Ribbon,

to see the conflict from the other side. If I’m honest, I didn’t personally sympathise

quite so much with the Royalist cause, and that probably comes through in the

book, but I think that says more about me than it does about anything else!

I

wanted to show what happened to the Royalist families who lost everything

because of their political allegiances (or in the case of many, just because of

their birth and background). For a period of time, families who had fortune,

status and property found themselves on the edge of poverty. Many were bankrupted

or exiled, and their property sequestered. Some never recovered. It was that

riches-to-rags story that I wanted to explore.

As

I researched Katherine and her family connections I became interested in those

who never gave up the Royalist cause. Under Oliver Cromwell’s increasingly

tyrannical Protectorship there were men willing to risk everything for the

return of the King. A whole underworld of conspiracy and intelligence continued

throughout the period, to this end. Of course, we know that, eventually, they

got their way, but it’s not the case that everything was restored with the

coronation of Charles II. How could it be? The legacy of the British Civil Wars

interests me and is something I’m thinking about for my next book.

The

only known portrait of a young Katherine Ferrers, now at Valence House Museum.

truths. a) Is this conscious and deliberate? b) Has it developed over time or

has it always been in your writing? c) How do you feel this is suited to

historical fiction?

I

don’t think this is conscious though I do sometimes question it. For example,

many people commented on the brutal opening scene of The Crimson Ribbon, and The

Silvered Heart also opens with a shocking event. I’ve wondered: how far is

too far? But I hope that if something feels true to me then the reader will

believe it too. I think I’ve become more confident in not shying away from

difficult or sensitive subjects and am learning to switch off that voice in my

head that worries about what people will think. I have to trust my instincts

(and sometimes, my editor!).

I

aim to present a picture that feels genuine (as much as it can ever be) and

life can be hard and brutal, then and now. I know I can be nostalgic about the

past – the kind of past that is so often presented in romantic costume dramas –

and there is a place for that too, but I try and bring a bit more grit and

grime. It feels closer to the truth to me, closer to history.

Katherine’s prize-winning short stories are also available in THE PAINTED CHAMBER.

[4] Are the settings, such as Markyate Cell, Ware Park, Nomansland Common &Gustard Wood, based on real places in England or purely from your imagination?

All

the locations are real places and most of them are mentioned in the popular

legend that the story is based on. Markyate Cell was the Ferrers family home

where Katherine was born. Her husband sold it off to settle debts in the 1650s.

In the book, the house becomes emblematic of all the losses that Katherine

suffers, and the disappearance of a lifestyle and future that she feels she was

born to. In a strange twist of fate, the real Markyate Cell has been out of reach

to me. During the time I was researching and writing, the privately owned house

was repossessed and has been on the market, without a buyer, for some time.

Though I’ve tried making enquiries over the last couple of years, I’ve been

unable to gain access. As far as I know, it is still standing empty. I still

hope I’ll be able to visit one day. So, if anyone has a few spare million…

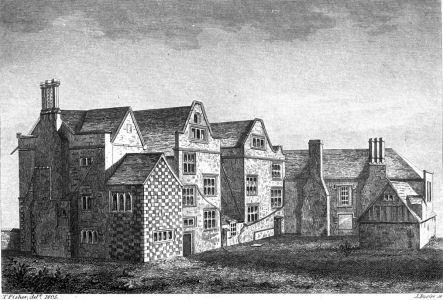

Markyate

Cell, drawn in 1805.

her time. Can you share other real examples of determined women from this age

you came across in your research? Did you have any of these models in mind when

creating Kate? And in

your research did you discover any real cases of highwaywomen?

I

certainly seem to have a fondness for strong female protagonists in my work and

I’m drawn to women in history who are extraordinary in some way. There are many

examples from the years of Civil War, on both sides of the fight. Elizabeth

Lilburne, wife of Leveller leader Freeborn John, is a favourite of mine, along

with Katherine Chidley, who became the leader of the Leveller women. The latter

is especially interesting because she attempted to galvanise a group of women

to express radical political opinions, including early shades of feminism, at a

time when that was a very brave thing to do. There are also some great stories

of women defending their homes from attack. Lady Brilliana Harley is probably

the most famous. She defended Brampton Bryan Castle during a three-month siege

in 1643. She was a prolific letter-writer; the surviving collection gives us an

insight into her life before and during the war.

Lady

Brilliana Harley

I

didn’t have anyone in particular in mind when creating Kate, but I always want

to dispel the myth that women were powerless in this period. Their political

influence was limited, but such examples show that they were far from the

weak-willed, subservient shadows that their absence in the historical record

sometimes suggests.

And

there were certainly female highway robbers working at this time, often

alongside men. Court records from a slightly later period show hundreds of

examples of women found guilty of highway robbery, so it’s not as unusual as we

might think, and it’s not too great a stretch of imagination to assume that the

same would apply in earlier decades.

I’m interested that you chose your heroine to share your own name! How did this

choice come about?

As

I explain above, she was a real person so I didn’t have a choice. In fact, I

found it very strange and slightly uncomfortable at first and wrote the entire

first draft using the name Kate. I needed the separation. In the end, I chose

to keep Kate as a pet name used by those close to her – she’ll always be Kate

to me!

Margaret Lockwood in the 1945 movie The Wicked Lady which is very loosely based on Katherine’s life (Katherine Ferrers NOT Katherine Clements…)

[7] I particularly enjoyed the political intrigues and wavering loyalties depictedwithin this historical period. What did you find most interesting in this

element of the times?

Because

I spent so much time working on the years of war while writing The Crimson Ribbon I wanted to look at

what happened next. The years of the Interregnum saw Republican ideals

flourish, waver, and then be quashed. I was interested in what happened to all

that extreme passion and fire that drove people to fight in the first place. But

I was also intrigued by what happened to those who stayed loyal to the

monarchy. Once I realised that the real Katherine Ferrers had links, through

her husband and the Fanshawe family, to the conspiracy networks that aimed to

restore the exiled Charles Stuart to the throne, it was a gift I couldn’t

ignore. I think restoration – or at least a nostalgic desire to return to a

better time – is a theme throughout the book, as Kate seeks to restore the

things that she’s lost.

King Charles II, painted in exile, 1653.

[8] Can you share a little with us of what you are working on next?Not

yet. It’s too early to say. But I will confess that I’m staying in the 17th

century. I’m not bored of it yet.

Katherine in the library – she’s so damned stylish!

Thanks to Katherine for such an interesting insight into her research and thinking behind her work.

THE SILVERED HEART is out tomorrow, published by Headline. There’s nothing much else going on tomorrow, the 7TH OF MAY, apart from Lydia Syson’s LIBERTY’S FIRE coming out and a bunch of other lovely books, so get yourself to the bookshop and snap it up because there’s really very little of interest going on tomorrow at all on the 7TH OF MAY…

You can find Katherine online here:

https://twitter.com/KL_Clements

and here’s the gorgeous paperback cover for THE SILVERED HEART which will be out next February: