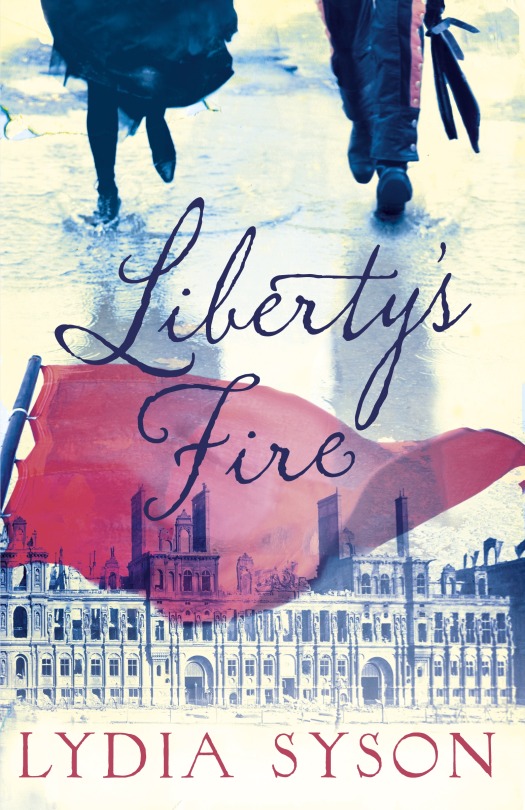

One of the nicest things about being published was that quite suddenly I found myself in touch via social media with an array of other published authors, many of whom are keen to connect with writers and chat about our business. One of these is Lydia Syson – one of those lucky occurrences where I stumbled across her Twitter page and discovered she’d written about the Spanish Civil War (with which I’m fascinated), thus asked to read her latest book. I then discovered she was an expert on C18th (and my latest book is set in that period) and that LIBERTY’S FIRE is set in a period of history I knew very little about: the Paris Commune of 1871. I had no idea the book was aimed at a Young Adult audience and – as usual with many brilliant YA books (see kerrydrewery for example) – it made no difference to me at all as an adult reader i.e. it was just a great read, compelling characters, wonderful moments in history, all beautifully written. I read it very quickly over a weekend, because I couldn’t put it down. Highly recommended for ALL readers, whatever age you happen to be…

So, I’m delighted to welcome Lydia to the blog to talk about LIBERTY’S FIRE, historical research, family history and more.

1. Having written non-fiction for an adult

audience, you then turned to fiction for a younger audience. What brought about

this direction in your writing? How do the challenges of both types of

writing compare?

It was partly practical: too many young

children! I had to be at the school

gates (luckily at the top of my road) three times a day and simply couldn’t get

to libraries to do research. At the same

time, I was often spending several hours each evening reading to each child in

turn – important and rare one-to-one time.

I loved going back to my own childhood favourites but also began to

discover lots of new authors who really impressed me – people like Mal Peet,

David Almond, Jenny Downham, Siobhan Dowd, Linda Newbery – all writing this ‘thing’

I’d not encountered before called YA. A

story idea began to form from bits and pieces that had intrigued me but hadn’t

made it into either Doctor of Love,

my biography of the eighteenth-century ‘electric doctor’ James Graham or my PhD

on poets and explorers and Timbuktu.

Very few children encounter the Enlightenment at school – which I think

is a terrible shame, and I couldn’t think of a more challenging way to develop

my story-telling skills than write for that demanding teenage audience. It’s a manuscript I need to revisit – I

really didn’t know what I was doing, and tried to cram too much in I think! –

but it got me a new agent, the absolutely brilliant Catherine Clarke, who

represents both some of this country’s best children’s novelists and also

writers of adult non-fiction, so I’m still able to keep my options open.

The challenges are quite different, I think. When you’re writing adult non-fiction or

academic texts you have to be absolutely meticulous about keeping track of all

the sources for your research, and structure your story round what you can prove. Historical fiction still demands a vast

amount of research, but I’m looking for something slightly different. There

comes a point when I need to absorb it in an entirely different, almost

unconscious way. Then I can let go of exactly

where ideas and images came from, and let everything compost at the back of my

mind. Eventually it melds together and

turns into something else entirely.

The texture of everyday life becomes much more

important when you’re writing fiction.

So I often end up spending ages finding out almost ridiculous things

like when coathangers were invented – surprisingly late, as it happens.

(*interrupts* I had the same issue whilst writing SONG OF THE SEA MAID, finding out when matches were invented – I needed to know how she’d light her way in a dark cave!)

But the pleasures of time and space travel,

parachuting and truffle-hunting, are shared by both. And I try very hard to work with many layers,

so some things will sow seeds for younger readers, but ring bells for older

ones. I don’t think the books really

have an upper age cut-off.

2. You’ve written about the Spanish Civil War,

World War II and now this conflict in 1870s France. What is it about war and

conflict that draws you?

War immediately offers high stakes and high

drama. People act more impulsively –

fall head over heels in love, run away from their families, betray their

friends, invite catastrophe. Obviously this makes great material for a

novelist. Both during and after every

war, conflicting narratives are created – by politicians, historians,

journalists – and these sometimes need to be challenged, particularly as we

leave the Cold War behind, or simply revisited.

The precise character of the Commune has proved exceptionally hard for

historians to pin down, and that makes it all the more interesting.

I’m interested in conflicts, or aspects of them,

which have been forgotten or rewritten, or are in the process of being elucidated

by new academic research which most people will never read. The plot of Liberty’s Fire was triggered by a couple of fascinating articles in

an academic journal by Dr Delphine Mordey about music during the Franco-Prussian

war and the Paris Commune, developed from her PhD on the subject, which was

also invaluable. I must say, I’m always

grateful to academics who aren’t sniffy about historical fiction!

3. As a writer of historical fiction, how do you

juggle fact and fiction in creating your narrative? What issues does this

create for you?

I suppose my rule is not ‘did this actually happen?’

but ‘could it have happened under those circumstances?’ So while I like to keep an overall historical

framework of events that is entirely accurate, within that I give myself plenty

of imaginative free play. I want to tell

the big story, but not at the expense of the ‘little’ one. So there are quite often things I find I have

to let go after the first draft because although they’re important for the

historical story, they don’t work in my own story: the stealing of the cannon

in Montmartre is usually seen as the ‘beginning’ of the Commune, but I ended

cutting that whole section from Liberty’s

Fire so that I could keep the focus on my characters rather than events. There’s also the problem of facts so often

being less believable than fiction, which I blogged about

http://www.lydiasyson.com/unbelievable/

after a reviewer doubted whether it was really plausible that Felix would run

away as she does in A World Between Us!

*interrupts again* I had the same issue with the Boer War letters in THE VISITORS, where some reviewers doubted they would ever have been written:

http://rebeccamascull.tumblr.com/post/78001947719/postal-censorship-during-the-boer-war

4. In LIBERTY’S FIRE, you write about the

short-lived Paris Commune of 1871. It’s extraordinary to think of Paris as a

kind of civil war zone throughout this time. How did you seek to recreate this?

How did your time in Paris – walking the same streets – contribute towards your

understanding of this moment in history?

As always, I shamelessly plundered memoirs and

accounts by people who were actually there. But about 20,000 of the Commune’s

participants didn’t survive, so we don’t have their stories. Many went into exile or had to hide their

involvement. But most importantly, many

were illiterate. One of the things for

which Communards were fighting was the right to a secular education for

everyone. Recovering working-class voices from history is always difficult. I

found it a particular problem while writing Liberty’s

Fire because even where such material existed or had survived, it wasn’t published

or translated – and my deadline was an awful pressure, and I read very slowly in French. I realised early

on that I had to be realistic about what I could achieve, and also keep

reminding myself I wasn’t writing a PhD!

Paris paving stones (& Lydia’s foot – she might have wanted me to crop this, but I like the fact that her foot is there! Adds authenticity!)

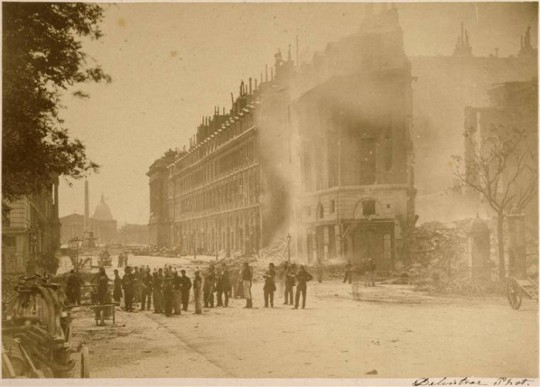

I pored over maps and photographs of Paris, fascinated

by how dramatically Haussmanisation changed Paris in the decades leading up the

France’s ‘terrible year’, and how quickly the city was rebuilt after 1871. But you

are quite right, it was definitely the trips to Paris which made everything

come alive. When you are standing on a French paving stone – small and cuboid,

rather than big and flat – you realise how much better they lend themselves to

barricade-building than their British equivalents. You walk past a tree and see the iron grill

that protects its roots in a whole new light. And it was incredible to stand by the Vendôme

Column, completely reconstructed, and imagine it in pieces in the square:

or pass buildings like the Hôtel de

Ville:

the Théâtre Lyrique or General Thier’s house and realise that, in a way,

they were fakes.

I spent a lot of time in different museums,

libraries and archives. Some I’d never

heard of before, like the beautiful Art and History Museum in Saint Denis,

which has an excellent series of rooms telling the story of the Paris Commune. The Museé de l’Histoire Vivante in Montreuil,

where I pored over photographs and even saw a Louise Michel doll, is even less

well known. (This museum has a fascinating history itself, having been established

in Montreuil by three leading Communists of the 1937 Popular Front on the 150th

anniversary of the 1789 French Revolution.) I was intrigued by the ‘souvenirs’ people

saved – ratbones:

and sawdust bread and

twisted shells and cartridges, which they displayed in little vitrines. I was lucky to catch an excellent lecture on

the women of the Commune and also walking tour about Commune photography.

And yes, I did indeed tramp the streets for hours,

looking at the light in the passages

and the layout of different neighbourhoods,

wondering about possible bullet holes in station walls, working out if and how

characters could get from A to B, where they should live, what they might have

encountered. I went to the cemeteries at

Montmartre and Père Lachaise:

where the last battles were fought among the

tombs and saw the wall where 147 Fédérés

– the Commune’s militiamen – were shot and thrown into an open trench. I became completely obsessed with cellar

ventilation shafts:

– in the final, bloody week of the Commune, Paris became

fixated with the mythical figure of the ‘petroleuse’ – working-class women were

accused of setting the city alight by throwing flaming bottles of petrol into

buildings, because they would rather see it burn than fall to treacherous

Versailles government. Everyone talked and

wrote about them, plenty of women were denounced, but none were actually

convicted of arson.

5. Take us through some of your other research

techniques that you used when writing Liberty’s Fire.

A very mixed bag!

Alongside academic texts and memoirs and accounts from many perspectives,

I read a great deal of relevant nineteenth-century fiction – from Zola,

Flaubert and Maupassant to G.A.Henty, Edward Bulwer Lytton and assorted obscure

evangelical Victorian ‘lady-novelists’ in which socialism is synonymous with

evil – and found I kept coming back to Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project. A song

I love was one of the things that started the whole thing – the Internationale,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kB9wELkGn9c&list=RDkB9wELkGn9c#t=30

which united Brigaders in the civil war and which we sang at my grandparents’

funerals, was composed after the fall of the Commune by the man who drafted its

policy on the arts. Two of my main

characters are musicians. So of course I listened to a fair bit of music, and

got to know the songs of the Commune – such the the Marseillaise, Le Temps des

Cerises https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_W0B6aUt3E

and la Canaille

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cEKXjHyaUio&list=RDkB9wELkGn9c&index=15

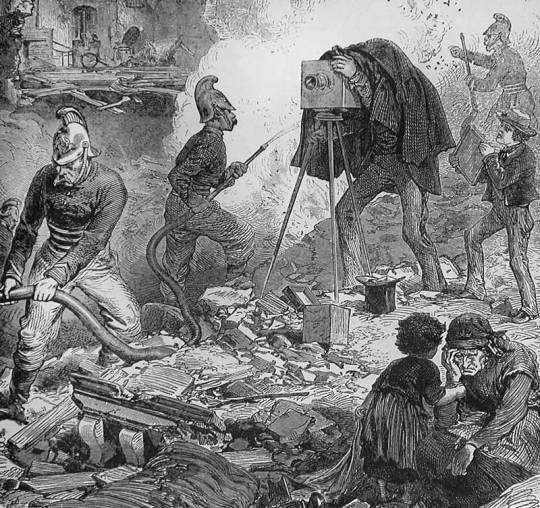

Paintings and prints were a great resource, particularly for

costume. One my main characters, Jules, a rich American, has been sent to Paris

to learn the art of financial speculation and instead discovers the twin arts

of flânerie and photography. So I spent hours watching online videos

about the wet collodion technique, which luckily is having something of a

revival right now among art photographers, and reading nineteenth-century

photography manuals.

Also, I keep all the material organised and write the

first draft with Scrivener. I couldn’t live without

it now, I must say.

Ruins of Paris, from the London Illustrated News, 1871.

6. I was particularly fascinated by the

photography sequences. I’d imagine this must have been one of the very first

conflicts in which photography was present to record it. What was it about

photography that attracted you to write about it and what part do you feel it

played in this conflict?

There is just so

much going on with photography at this moment – issues of representation

and interpretation, art, truth, fakery, propaganda, memory, censorship – it was

an irresistible theme…I owe a lot to the International Brigade Memorial

Trust’s chief photographer, Marshall Mateer, who sent me some articles after a

conversation we’d had about some of this when we were both on an IBMT trip to

Spain for the 75th anniverary of the Battle of the Ebro, just as I

was starting work on Liberty’s Fire.

Actually, a surprising number of wars had already

been photographed – most famously the Crimean and the American Civil Wars – and

small, photographic cartes de visite were

all the rage throughout the 50s and 60s.

There were technological limitations, so shots are always before or

after, never during battles. Extraordinary

images were produced during the seventy-two days that Paris governed itself,

though it’s not always easy to determine the photographers’ political position,

or exactly why the pictures were taken. There

are carefully staged photographs of Communards posing by well-built

barricades. Others record the deliberate

destruction of the Vendôme Column, the city’s most potent symbol of

Empire. And some of the first morgue

photographs were taken at this time, devastating pictures of Communard corpses

in coffins, probably recorded for identification purposes.

Barricade at rue Sommerand / boulevard Saint-Miche

See here for more stunning Commune photographs:

http://www.pariszigzag.fr/histoire-insolite-paris/photos-paris-la-commune-1871

After the fall of the Commune, during which

invading government forces slaughtered 20,000 people, and took twice that

number prisoner, photography becomes even more interesting. Not only were photographs used by the

authorities to arrest suspected Communards, an early example of photography in

criminology, but one man, Ernest Eugène Appert, used mugshots he took of

prisoners to create a series of convincing photomontages called ‘The Crimes of

the Commune’ – faked scenes which include women in prison drinking while they

awaited trial, the execution of the Commune’s hostages, and even the

assasination of two generals in Montmartre when the uprising kicked off –

photoshop avant la lettre.

These made such effective anti-Communard

propaganda that eventually the government, which kept strict control over all

printed images in circulation, banned them for continuing to ‘disturb the public

peace’ at a time when official policy was to try to forget the Commune had

ever happened – hence the rebuilding. But before that time, horror had collided

with pleasure: the open ruins of Paris quickly became a vastly popular

aesthetic spectacle. Crowds of tourists from

the provinces and abroad flocked to experience what Gautier called ‘the

picturesque of rubble’, and to ponder on the French capital’s Babylonian fall,

while condemning the wicked Communards they held entirely responsible. Thomas Cook quickly cashed in on this. There were even guidebooks to the ruins. Almost overnight, Paris had acquired the

grandeur of ancient Rome.

According to Gautier and others, including the

Illustrated London News, photographers were everywhere in these early days, and

criticised by some for getting in the way of the firefighting:

‘One sees …the carts which photographers use

as laboratories parked outside the slightest picturesque ruin.’

Paris, rue Royale, May 1871

7. You say at the end of the book that your great–great–grandmother was N. F. Dryhurst. How did you discover this part of

your family history? When I was writing THE VISITORS, I discovered a family

link to hop farming and became temporarily addicted to ancestry websites! Did

you fall headlong into researching your family tree as I did?!

To be honest, I’m slightly scared at how

addictive this might prove! On my mother’s side of the family, I’ve always

known that I was descended from a long line of radical activists. I remember a

huge, handwritten family tree that used to come out at big parties when I was a

child – my grandfather was one of thirteen. When my first novel came out, the

iAuthor platform had just been released and my publisher had the brilliant idea

of making an enhanced iBook of A World Between Us, with all kinds of Spanish

Civil War background material, from interviews with historians and the last

surviving British Brigader, to archive photographs and letters and even music,

and they wanted to include a family tree and photographs.

http://www.lydiasyson.com/multi-touch-ibook/

I have been digging around a bit since then, and

one thing that’s struck me is that the women in the family have been photographed

by some quite exceptional photographers. In the LSE archive is a photograph

which belonged to George Bernard Shaw showing Dryhurst with her two daughters. That was taken by the Victorian celebrity

portrait photographer, Frederick Hollyer.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/f/frederick-hollyer/

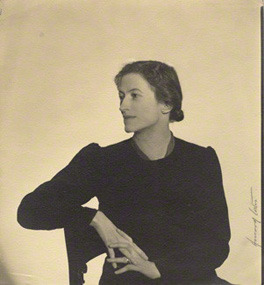

Sylvia Lynd, my great-grandmother, was photographed by Howard

Coster, unusually, as he was known as the ‘photographer of men’:

while the

well-known Communist photographers Ramsey & Muspratt and Edith Tudor Hart

produced portraits of quite a number of family members, including my own

mother.

http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw163641/Sylvia-Lynd?LinkID=mp57079&role=sit&rNo=1

In the last few years, there’s been a surge of

academic interest in another relative, the scholar and polymath Moses Gaster, described

by one library as ‘one of the most significant figures in modern Jewish

history’:

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/special-collections/moses-gaster

and a

fascinating figure. My great-aunt

Bertha, a wonderful story-teller, always used to say of her father: ‘He looked

like God, he acted like God, we thought he was God, he thought he was God. Maybe he was God!’

(*interrupts yet again* I love that!!)

Some of my extended family have been following

developments with interest, and last month about twenty of us met for a Moses

Gaster day, starting in the East End with a talk at Bevis Marks synagogue where

he was leader of the Spanish and Portuguese congregation and ending at the

British Library, being shown the highlights of the extraordinary manuscript

collection he sold in 1927 to make ends meet.

http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelplang/hebrew/manuscripts/gastercoll/

8. Can you share anything about what you’re

working on next?

I can tell you its working title – Blackbird

Island – and that it’s set in the

Pacific around the time the Communards were exiled to New Caledonia. But that’s the only point of connection with

Liberty’s Fire. And I’m plundering my

husband’s family history this time!

Lydia, let me shake you by the hand and THANK YOU for a completely absorbing and fascinating tour around not only LIBERTY’S FIRE and the Paris Commune, yet also for giving us such a wonderful insight into your research and writing process, which shows what high intelligence and profound integrity you bring to the creation of your historical fiction.

So, readers, WHATEVER AGE YOU ARE, go read Lydia’s books for a beautiful marriage of fact and fiction.

LIBERTY’S FIRE is published by Hot Key Books this Thursday May 7th.

You can find Lydia online here:

https://twitter.com/LydiaSyson

and she also writes for the excellent History Girls:

http://the-history-girls.blogspot.co.uk/

https://twitter.com/history_girls