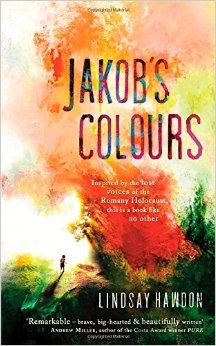

Delighted to welcome debut novelist (yet highly experienced writer) Lindsay Hawdon to the blog, with an interview about her beautiful debut JAKOB’S COLOURS. Here’s the blurb:

Austria, 1944. Jakob, a gypsy boy – half Roma, half Yenish – runs, as he has been told to do. With shoes of sack cloth, still bloodstained with another’s blood, a stone clutched in one hand, a small wooden box in the other. He runs blindly, full of fear, empty of hope. For hope lies behind him in a green field with a tree that stands shaped like a Y. He knows how to read the land, the sky. When to seek shelter, when not. He has grown up directing himself with the wind and the shadows. They are familiar to him. It is the loneliness that is not. He has never, until this time, been so alone. ‘Don’t be afraid, Jakob,’ his father has told him, his voice weak and wavering. ‘See the colours, my boy,’ he has whispered. So he does. Rusted ochre from a mossy bough. Steely white from the sap of the youngest tree. On and on, Jakob runs. Spanning from one world war to another, taking us across England, Switzerland and Austria, Jakob’s Colours is about the painful legacies passed down from one generation to another, finding hope where there is no hope and colour where there is no colour.

This is what I had to say about it:

“A haunting book, dealing with a little-known part of history, told in luminous and poetic prose.”

neglected part of history – how did you

first learn of it and what finally prompted you to craft a novel about it?

I

began this book simply with a small boy running, that was all, and then slowly

layers were added to it. In a sense

writing is very much about reading too – you write a sentence down, then read

it, have an emotional or thought provoking response to that and then write down

another sentence. I knew the world Jakob

was running from wasn’t

a safe one and for a while I very much stayed clear of the second world war

because I simply didn’t

have the confidence nor felt I had any claim to write about it. But then I started to think of Jakob coming

from no home, from having no place to run to, or a place to return to and that

got me researching Romany past and present which led me back to WWII. I was intrigued that the stories we always

hear about were Jewish ones, because between a half and one and a half million

Romani lives were lost by 1945. The

exact number isn’t

known. The Nazi genocide of the gypsies

was only officially acknowledged in 1982 and it was not until 14 April 1994

that the U.S. Holocaust Memorial held its first commemoration of gypsy victims. The silence of this information was what

interested me, how was it that we knew so little about the fate of an

entire race? Then when I started to research the Romany past I realised that

for them WWI and WWII were just two moments in time when they had to face

persecution, no more no less that anything they had faced before. After WWII Roma people had no time to linger

on the atrocities that had taken place, to pause and claim justice, they were

too busy surviving the next wave of persecution that came their way.

I

suppose in the end what I wanted to do with this book, was to strip back

everything, to see what you were left with if you had to face the very worst,

as I think they have done.

I think firstly that Roma people tend to have an aural

history of storytelling, not a written one, so not much is documented and

secondly that sadly persecution didn’t stop for them when WWII ended. It began long before, when they were first

cast out of India and it has not ceased since then. So there was no time to stop and reflect on

the horrors that had unfolded. They were

thrown into the next wave of things to contend with. Still, to this day, we are distrustful and

fearful of them as a race. At best we romanticise the gypsy lifestyle. Mostly they are tolerated in times of prosperity, cast

out in times of recession. But where are

you to go when you have no land to call your home?

jumps between different time periods. Could you explain how the decision to use

this narrative style came about and how it developed in the planning stages?

Also, how does it contribute to the novel’s themes?

I don’t think I consciously sat down to write a

fragmented novel, but I wanted there to be a pace, a breathlessness, to the

story, for everyone to be running from something, and for that to be reflected

in the tension of having to piece bits together. The characters are disorientated, and the

life of the Roma is often disorientating, as is war. I think I wanted the reader to be

disorientated with them, the three fragmented stories only gradually

unravelling, rather like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, the whole story only

revealing itself at the very end. Because this

was a first novel I was very much learning to write as I went along. I tend very much to picture whole scenes and

then feel my way through them, so perhaps that too explains the

fragmentation. That and lifestyle. I was very much grabbing moments to write

when and where I could.

of research you undertook? e.g. to evoke a sense of place in Austria and

Switzerland; and to render the Yenish way of speaking?

I did a lot of research in the usual way, found

everything I could to read on Roma culture and history, and also mental

institutions in the 1930s.

But in a more

practical way I also visited several gypsy fairs in England and on my travels I

have often come across Roma people and spent time with them. In Albania, Kyrgyzstan, most of Europe. On my travels I have often slept rough, or

taken long treks across difficult terrain, mountains, deserts, forests, so I

relied on the memory of those experiences to evoke in my imagination the

reality of living a life beneath the stars.

Then as an eighteen

year old, travelling around Europe in a camper-van for a year, I had been to

the concentration camp Mauthausen in Austria, and it had always remained a very

vivid memory for me. And more recently I

visited The Killing Fields in Cambodia with my two young boys and it really

struck me as we wandered around the place that despite the atrocities that had

taken place there, and despite the pieces of bone and tooth that had been

washed up from the ground with recent rainfall, that still lay on the path on

which we walked, the overriding atmosphere was one of peace and love. I wanted to explore how it was that in those

final moments it is not the horror or the brutality of death that endures, but

love, perhaps because it is the last thing that we feel when we pass from this

world to the next. I wanted to explore

in the writing if a moment of brutality could be overridden with the love of

the people that surrounded it.

Like Jakob, my two boys and I are currently travelling the globe on a six month trip to seven countries in

search of seven colours, the natural pigments made by the first colour-men, the

first artists, raising money for the charity War Child as we

go. We are The Rainbow Hunters.

We have travelled to Kashmir to find saffron

yellow, arriving in Srinigar one month after the floods that had swept through

the city, still a mess of

water-logged mud and silt, people wading knee-high through stagnant pools trying to salvage

what they could from the rubble.

We went on from India to China, where

we trekked to ancient temples in search of celadon green, a mystical glaze that

covered the porcelain of the Ming dynasty.

In Italy we found cremona orange, a secret varnish

that has coloured the Stradivari violins.

In New Zealand it was the colour violet, which we found

in a lichen that grows on the trees in the fjord land of Midford sounds and in a sea snail, that can weep violet tears. And in the red deserts of central Australia

we found red ochre in an eerie dried up river bed of the MacDonald Ranges. In Chile, we searched for the colour blue, off to a lapis lazuli mine that lies 4200m up in the

high Andes. And our quest finishes in

South Carolina with the indigo plantations of Charleston.

The idea began as a story I used to tell the boys when they were little, beneath the covers of pre-night slumber. A somewhat epic tale that lasted for years, where we rode

on horses, across

deserts and snow capped mountains in search of the stolen colours of the rainbow, very similar to the one Lor tells Jakob in Jakob’s

Colours. When my novel was accepted for

publication, we were able to make the journey into a reality. I had always wanted travel to be part of the

boys’ schooling. I had already taken them

on a year’s trip around S/E Asia and Australia when they were 5 and 8. But I wanted this trip to be more than just

another travel trip. I wanted the boys to feel they were contributing to

something they could relate to. Already

they had visited the Killing Fields as I’ve mentioned and they had seen third

world existence, seen children living lives no child should have to live. So on

this trip we also wanted to raise money for War Child as we went, through

sponsorship, through campaigning.

War Child works in countries that have been devastated

by armed conflict and helps children suffering the worst effects of violence;

child soldiers, victims of rape and abduction, disabled and street children. They provide vital care to a traumatised

child and help them to rebuild their lost childhood. Their aim is a

world in which the lives of children are no longer torn apart by war. So hence the rainbow. Hence,

the hunting.

If you

would like to donate something please go to

https://www.justgiving.com/Lindsay-Hawdon

This is your first novel – can you

describe the differences for you between the experience of writing non-fiction

and fiction?

A

column is much more constrained in terms of freedom of style and length, and I

am writing about things that have actually happened so they have a factual

constraint too. But you still have to

find a way to turn an article into a story, for it to have a beginning, middle

and an end. The reader still has to want

to read on from that first sentence to the next. With novels you are free to explore anything

you want. There are no constraints, just

this vast blank page, the prospect of filling it both terrifying and

thrilling. But I loved that freedom,

where you can open your imagination up to possibility. Later you have to pull back, draw everything

in tightly around itself, and I love that part of writing a book – when you

have words safely on a page and like a sculptress can pick and hack away at

making a line as you want it. This is my

first book. I’ve

very much learnt how to do it as I’ve

gone along, muddled my way through it in every sense of the word.

pipeline and can you share anything about it?

There is and it seems to have arrived very well formed

and I’m feeling really excited about it.

At the moment I’m researching and stumbling around a bit, catching

moments here and there to write as we travel.

At the moment its set in a contrasting world of snow and desert, and

explores what happens to people when they are brought up in a distorted

reality, the difference between our inner worlds and our outer ones, but I

won’t say anything more about it for fear it might well disappear into the

ether!

Thanks so much to Lindsay for her fascinating answers and for giving me an insight into an important yet overlooked part of history.

You can find her online here:

https://twitter.com/Lindsayhawdon

https://www.facebook.com/Lindsayhawdon

http://lhawdon.co.uk/www.lhawdon.co.uk/Home.html

JAKOB’S COLOURS is published in hardback & e-book this Thursday 9th April by Hodder & Stoughton.

And here’s that web address again if you’d like to donate to the charity War Child: