I’m thrilled to introduce on the blog today the excellent novelist Joanna Briscoe. I read her latest book TOUCHED and was hooked from the first page. Beautifully written, it’s a spooky and enveloping tale of a perfect English village with sinister undertones, set in the 1960s.

Here’s the blurb:

Rowena Crale and her family have moved from London.

They now live in a small English village in a cottage which seems to be resisting all attempts at renovation.

Walls ooze damp, stains come through layers of wallpaper, celings sag.

And strange noises – voices – emanate from empty rooms.

As Rowena struggles with the upheaval of builders while trying to be a dutiful wife and a good mother to her young children, her life starts to disintegrate.

And then, one by one, her daughters go missing …

I asked her some questions about TOUCHED and she was kind enough to answer them, within her crazily busy schedule, and also provided some wonderful images of Letchmore Heath, the gorgeous village where – in fiction at least – everything is not as it seems…

[1] Your writing contains some beautiful, poetic language e.g. the hueof shadowed walls; laughing light; had rain for hair. Do you tweak these in a

later edit or do they simply come to you as you write?

Reading these phrases you’ve picked out surprises me because I’d

forgotten them, and I like them! It’s very strange, but with this novel, I

almost wrote it straight out, in terms of the prose and what I saw as the plot

and structure, though I then had a proper structural edit from my publisher.

That is not my usual way. I do edit, tweak, cut, re-write, change a lot. I do

believe novels are more re-written than written. But I had a short deadline for

Touched; I was very inspired by the commission, and I had guidelines from my

editor – for example, clearly defined characters, and not too many of them; a

clear plotline without a big subplot. The structure was easier than a longer

novel, as I had to be disciplined as I went, and I wrote it in a fever of

inspiration, and the prose itself was unusually fast for me. I think I sort of

shocked myself, with the panic over the deadline, into a vivid prose style that

took some risks. I’ve learnt a lot about writing faster!

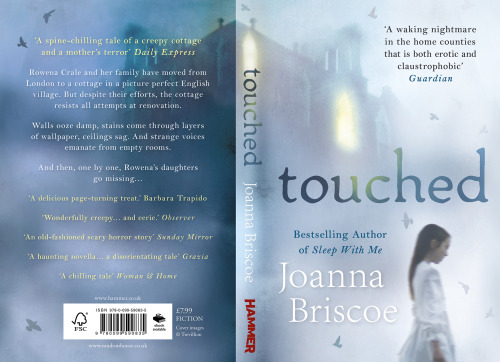

The village green at Letchmore Heath, the ‘perfect’ English village, Joanna’s early childhood home.

[2] One of Rowena’s daughters is called Eva and she is an extraordinary character. How did you project yourself intosuch an unusual mind and also come up with her mannerisms?

You are now making me deconstruct what was largely instinctive, but it’s

interesting, with distance, to do so. She was my first character. I simply saw her on a village green the moment I

started thinking about a supernatural story: a shabby girl dressed as a

Victorian, against bright grass. With her slightly dirty appearance and dissonant

contemporary aspects, she is a creepy character, who looks somewhat like an

apparition.

As for her mind and

mannerisms, I just realised that beneath this strange exterior would be a

sensitive and in many ways normal mind, and that she had decided to rebel and seem

strange – even ‘mad’ – partly for her own purposes, and partly as an expression

of her anger about both her grandmother’s treatment, and the favouring of her

more beautiful sister simply on the grounds of her looks. Some of her oddities

are semi-inventions of her own. For example, she doesn’t wholeheartedly believe

in her imaginary friend, but he allows her further rebellion, and the freedom

she then secures herself.

In her anger, she finds

another world that appreciates her more than her family and home.

Her voice is strange,

simply because of odd emphases. I discovered that if I put words in italics

where they would never normally be used – even on tiny, entirely insignificant

words – it made for a very odd effect, and this contributed to her unique speech

patterns. So she does appear strange, slightly disturbed, but clearly

intelligent. And when we see the real, relaxed her, for example with Pollard,

we see that she isn’t quite as strange as she’s pretending to be.

postcard perfect, on the surface. So what is it about them that you feel makes

them ripe for creepy stories like this one, or the film based on John Wyndham’s

‘The Midwich Cuckoos’?

Oh, this setting occurred to me the moment I was asked to write a novel

for Hammer/Arrow. I had recently returned there, in adulthood, for the first

time. It was a village I’d lived in till I was four, and remembered with

absolute – even creepy – clarity and accuracy. I changed some aspects, but it’s

a thin disguise. The village is so very very pretty with its green and its pond

and its war memorial, so quintessentially English, it just makes one wonder

what’s going on underneath. There has to be darkness in all that brightness.

Beauty, as in my character Jennifer, and my village setting, dazzles, and

people respond to the surface, so all sorts of things can go on underneath an

appealing disguise.

Such villages are the

opposite of more common gothic settings – moors, misty places, creepy halls,

run down houses – so I wanted prettiness and the bright sunshine so I could

upend a convention. I thought it would be interesting to write about haunting

where one wouldn’t expect it. I played with several horror tropes, both

intentionally and naturally.

parenting in this novel seem frighteningly accurate. What aspects of this theme

do you find most interesting to write about?

The novel is almost all set in 1963, and I wanted to explore an era that

gave children so much more freedom than today’s children have. There were not

the same fears, nor the same sense that parents must organise children’s time.

But then this freedom could also be abused, as in the case of my novel. I also

wanted to explore how an intelligent mother of five could be absolutely worn

down, to the point where, frustrated and exhausted, she has little control over

her children. The father plays no active role in the parenting, reflecting

something of that time. He also shows favouritism, elevates the male, and is

very aware of social conventions.

On a psychological

level, I was fascinated by an essentially powerless child – Eva – and how she

might rebel, through anger and manipulation. Children’s powerlessness can be

absolute. Eva only finds her real liberation later. And then, of course, her

favoured sister is, in very real terms, powerless as well.

Mrs. Pollard displays

what we would term ‘baby hunger’, to an extreme degree, driving her to commit a

crime. Her urge for motherhood is especially strong in the face of Rowena, who

has five children and, to Mrs. Pollard’s mind, neglects them.

your narrative? And what do you find most appealing in writing about the

past?

I always thought I couldn’t write a historical novel, and yet of course

1963 is now a very long time ago! But I have early childhood memories of the

late sixties, as well as much cine film taken by my father. I intentionally did

no research as I wrote the novel, finding I could inhabit a slightly surreal

sixties world quite easily, based on commonly known images, films, novels, and

personal memories, and then I added a little research and checked facts, along

with a very good copy editor, afterwards. I liked exploring different attitudes

towards child rearing, women’s roles, and, in the early sixties, a society and

culture that nodded back to the fifties and even the war period, with the

Swinging Sixties just about to change everything.

I also loved the

aesthetic. I loved describing all the gingham dresses, lemon yellow cardigans

and house coats, Alice bands and home knits, along with the ‘modern’ décor

chosen by Rowena, and the food of the time. That was really fun, and

satisfying.

effective ghost story? Are there any rules or imperatives to include?

Don’t include the ghosts! I mean it. As Roald Dahl said, ‘The best ghost

stories don’t have ghosts in them.’ The story can be riddled with presences,

but they’re more effective if they appear non-visually, or in the effects they

cause. Anticipation is important, and so is subtlety. It’s all about terrors

glimpsed or imagined. There’s a fine line between the psychological, and the

creaking ghost thumping around, and it’s hard to handle this so it doesn’t

inadvertently stray into comedy! You have to balance post-Freudian thinking and

readers’ desire for some full blooded hauntings.

Well, it’s complicated, because I’m in the strange position of having

two manuscripts that aren’t quite finished. Distance does wonderful things, and

I’m in the middle of – I hope – a final draft of one of them, where I’ve

changed so much, including the setting, the person it’s written in, and the

protagonist! It’s been a bastard to write, this one. It’s only now I’m speeding

ahead, after so much work, so many wrong directions. I think – again, I hope –

it’s finally found its form. Actually, I’m sure it has. I’m finally excited. I

don’t want to say too much, because then I don’t feel the same urgency to write

it, but it’s set in London, it’s contemporary, and it involves an artist in

crisis who gets help from the most disastrous source. There. I’d better finish

it.

Thanks so much to Joanna for her fascinating answers, which give us such an interesting insight into her writing process. And I wholeheartedly agree that some books are a ‘bastard to write’!! But hopefully, the finished product goes out into the world like a swan on a lake, with all the hard work going on underneath and out of sight…

You can find Joanna on social media here:

https://twitter.com/JoannaBriscoe

https://www.facebook.com/joanna.briscoe.7

and on her website here:

TOUCHED is out in paperback this Thursday, 26th March, published by Hammer/Arrow Books/Random House.